Her whole life, Mubanga Kalimamukwento has asked why. She didn’t accept the fairytales she heard as a child. She didn’t understand why she had to cook nshima “like a girl.” Some questions would prove harder: for many years, she wondered about the death of her family. First, her sister when she was six, then her mother when she was 10, then her father when she was 11. It was not only their demise but the secrets that followed that left her unmoored.

Her mother was a quiet teacher who loved to read, and that memory of her is trapped in time. “I will never know her beyond that age, but I will also never know her as an adult,” Kalimamukwento told me. “What that means is that she exists in a very specific way in my mind.”

Over the years, relatives shaded contrast into the blurry picture. She suspects her mother would not have liked her debut novel, The Mourning Bird. It is a bildungsroman, set on the harrowing streets of Lusaka, in which a girl’s world fractures after she is orphaned. “I don’t think she would have believed that it was necessary for me to reduce these observations into a story,” Kalimamukwento said. Still, her mother is the “god” of her writing. “I think the only reason that I became a writer, the only reason I became conscious of the things that were going on around me was because she died and because she died so young. And there was a sense of unjustness that I felt about it.”

Her death freed a storytelling hand when they were asked in English class to write about their holidays. It was her first Christmas without her mother and she was close to tears. But her teacher told her she could write anything she wanted, it need not be true. “That opened my mind up so much. Like, I can step out of my reality and make anything.”

Only when her grandmother read The Mourning Bird did she open up. She told Kalimamukwento that they tried everything to save her mother. It was her way of saying: Your mother had HIV. By then, Kalimamukwento had had decades of survivor’s guilt, wondering why only she lived through the then unnamed fate.

Before the arrival of antiretroviral treatment, a HIV/AIDS epidemic stormed Zambia in the early 1990s. The descent from diagnosis to death was quick, and connotations of promiscuity fueled the stigma. Abstinence messages and advertisements littered the country, cautioning people to check their statuses, while others implored them not to judge based on appearance. But the conversations bore no empathy. There was chatter but no real communication. The cost of dehumanized sensitization was mighty. When she visited her mother’s grave again as an adult, she struggled to navigate the crowded site.

Although she now understood the difficulty in deciding how much to share with a child, the confusion then was no better. To go from having a whole family to being alone, and within a few years, would traumatize an adult, and certainly a child. “There comes a point where some things need to be said, and you need to assess: what is the cost of silence? What is the cost of keeping certain things secret? Secretness is not the same as sacredness, and I think sometimes those two concepts are conflated.”

She knew she was only one person in the overwhelming statistics of children orphaned by the disease. Children whose care often fell to extended family, many of whom, unlike hers, could not bear the burden. The thought stayed with her: “Any of those children could have been me, basically. I do consider myself lucky, because here I am to tell their story, and many of those children weren’t able to tell their story.”

It was important for The Mourning Bird to resist the mindless perception that street children come out of nowhere. Her protagonist, Chimuka, gets a real, contextualizing story. She barely crosses girlhood when the deaths of her parents define her and her younger brother Ali in grueling ways. The novel’s considerations are difficult — loss and death, suicide, addiction, poverty, and, heavily, sexual assault — and Kalimamukwento metes out a relentlessly candid treatment, a staunch, often breathless realism. It is a world of pervasive cruelty and insidious indifference. Survival takes different forms, from the theft and sex work of grim street life to the small, ugly respite of “glue” — inhalant abuse — until all that tether Chimuka to her former life are swathes of memory. The novel teases a frightening resignation; in one of the more unsettling scenes, after an assault by a police officer, Chimuka narrates almost offhandedly: The tears did not come that time.

Kalimamukwento chose a clear-eyed tale of survivors and victims still reaching for agency even at the mercy of circumstance. But in a publishing industry shaped by upper middle-class tastes, she had to fight for even that. An agent once sent detailed feedback: they would reread and sign on the book if Kalimamukwento deleted the first six chapters and began the novel from the tragedy that offsets the lives at the center. Kalimamukwento said no easily: “I don’t want her story to just be her worst days.” The same manuscript later won the 2019 Dinaane Debut Fiction Award and was published that year.

Kalimamukwento resists loss as a sole descriptor. She lived in Zambia most of her life, first in a teacher’s compound in Luanshya, then a farm in Lusaka. Now she’s in the United States, in Minnesota, where she finished an MFA at Hamline University and now lives with her husband and kids. There, she is a mentor at the Minnesota Prison Writing Workshop. She throws her heart into her passions. On our video call, while brandishing the character sticker on her water bottle, she told me that she loves Angelica, the entitled little blonde girl in the ‘90s cartoon Rugrats, because she loves difficult women. It is a rebellion she hasn’t come to terms with — even though her girlishness belies her grit and she only wrote a book after someone told her she couldn’t. She may see it, too, in her son, who is as precocious as she was.

As a child, she was a talker. “Don’t you get tired?” her mother would say. Her parents gave her newspapers to read from start to finish just to keep her quiet. She was fascinated by the obituaries in the Zambia Daily Mail, the grief and love so vast in a picture and paragraph. She was reading the African novels her mother taught, as well as her aunt’s Danielle Steele collection, so she treated the obituaries as prompts, drawing out bigger stories. She wanted to be Miss Zambia because she thought the 1992 title holder, Elizabeth Mwanza, was the most beautiful woman she had ever seen. She adjusted her aspiration after her father told her that the 1997 Miss Zambia, Tukuza Tembo, was also a lawyer.

After her mother’s death forced her imagination open, she began writing seriously at 13 and submitted work for a competition run by KTV. Later, in tenth grade, she started a magazine with her friends after their school first got computers. At 17, she began writing a story, a variation of which would become her debut novel. She was confused by signboards in Lusaka telling people not to give to beggars because it would encourage begging. “Maybe I’m naive,” she recalled thinking, “but I don’t believe that there is a person who would ever want to be at somebody’s mercy in that way.”

In high school, she kept her father’s story about Mwanza in mind and joined the debate team. Her club matron called her “counsel,” and that, along with other good mentors and John Grisham novels, infused her with the final confidence to pursue Law. She earned that degree at Cavendish University, where she thrived. She became a criminal defense attorney and State Advocate at the country’s National Prosecution Authority, with a focus on policy change, prison reform, and human rights. The day we spoke in February, she said during our interview, was her twelfth anniversary of being called to the Zambian Bar.

Even in that field, she believes she is telling stories. “The Law is its own language,” she explained. “When you’re a litigator, your job is to listen to the story of your witnesses, to help them frame it so that, when they tell it, they can be understood.”

Back then, in the rush of life and career, she’d forgotten about fiction, but as her legal earnings allowed her to buy all the books she wanted, she finally thought of writing hers. She might not have risen to the challenge were it not for a writer friend who, working on a book of their own, dismissed her ambition. “Sometimes mentors,” she said, “but sometimes haters also.”

Fiction, Kalimamukwento told me, is her “final form” of storytelling. The books and manuscripts have been rushing out: four more in the last three years, excluding The Mourning Bird. She branched into poetry with the 2022 chapbook unmarked graves, published by Tusculum University Press, and into nonfiction with the manuscript of Another Mother Does Not Come When Yours Dies, a hybrid, multi-lingual collection of essays and poems shortlisted for the 2023 Center for African American Poetry and Poetics (CAAPP) Book Prize.

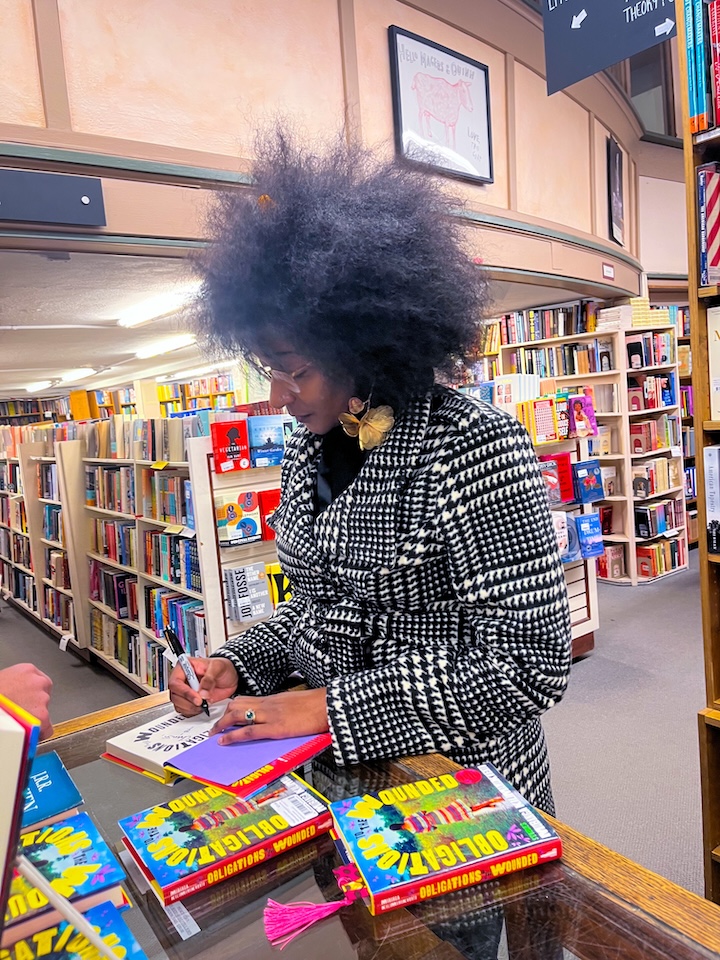

A short story collection, Obligations to the Wounded, written when she first arrived in the United States in 2018 for the Hubert. H. Humphrey Fulbright Fellowship, was released by the University of Pittsburgh Press last year. The book centers Zambian women at home and abroad as they negotiate and tussle with religious expectations, loss, race, sexual abuse, identity, immigration, and a grueling AIDS epidemic. It garnered acclaim. Booklist called it “a sensitive work of compelling juxtapositions: neat and raw, soft and tough, victimized and empowered.” The novelist and Doek! editor Rémy Ngamije hailed it as “The work of a writer in the full flow of her storytelling prowess.” For the collection, she became the first Zambian and African to receive the Drue Heinz Prize, in the award’s 43 years of existence. The stories went on to win a Minnesota Book Award and a Firecracker Award this year, and landed on the longlist of the Carol Shields Prize for Fiction. Next year, another novel, The Shipikisha Club, which won the 2024 Dzanc Books Fiction Prize for its story of a working mother in Kabwe, Zambia, on trial for the murder of her husband, will be published.

Few Zambian writers have reached international recognition. Despite its vibrant oral storytelling tradition, its written literature has, historically, a relatively tenuous foothold on the continent. Earlier successes — like Dominic Mulaisho’s Tongue of the Dumb, the first novel by a Zambian to garner major readership, released in 1971 under Heinemann’s African Writers Series, and Binwell Siyangwe’s A Cowrie of Hope, published in 2000 — did not lead to a full wave.

Things only began to change in the last decade. Namwali Serpell published her debut novel The Old Drift in the same year as The Mourning Bird. Cheswayo Mphanza won the Sillerman First Book Prize and earned a National Book Critics Circle Award shortlisting for The Rinehart Frames, his intertextual poetry collection, and Kayo Chingonyi’s poems in Kamukanda won him the Dylan Thomas Prize and Somerset Maugham Award. (Like Kalimamukwento, Chingonyi lost both his parents to HIV-related diseases, and his second collection Blood Condition considers both personal and uniquely Zambian griefs.) Preceding them, as one of the earlier important contemporary voices, is the novelist and short story writer Ellen Banda-Aaku. Predictably, the newer writers leading the charge are all, except Banda-Aaku, diaspora writers.

Their country may have sparse literary capital, but Zambians are still writing. “The stories are there, but the spaces and the support aren’t quite as there yet,” Kalimamukwento said. “I’ve read academic pieces that talk about the catching up that Zambia has to do. But since we already know that, my hope is that the spaces will be created. I think what Zambia needs right now is less talking and more action.”

Experience at Waterstone Review, a year-long internship at Shenandoah, and time at Doek! equipped her to do just that — create a soft landing for Zambian writers. In 2024, she founded Ubwali, a volunteer-run non-profit, where she is editor-in-chief. In its one year, the magazine has released four issues and published over 60 writers. In partnership with Shenandoah, it established the Hope Prize, named in honor of Kalimamukwento’s mother. It also created the Hope Prize Mentorship and the Ubwali Masterclass, to equip writers with literary tools.

Although it accepts the occasional non-countryman, Ubwali is deliberate about its Zambian writers. It is based in Minnesota, where Kalimamukwento lives, though its other editors reside in Zambia. She told me that she wants literary infrastructure based primarily in her country: a robust traditional publishing industry, more literary magazines, more bookshops.

“The stakes are different for us,” she said. “A lot of our literary counterparts have other magazines in those countries. My dream is that when someone goes into a bookstore and they look at the African fiction section or just African book section, whether it’s poetry, fiction, or creative nonfiction, there would be so many Zambian writers that they don’t know all our names.” And if they find her books, if they find The Mourning Bird, perhaps they could see also in the story of the orphaned little girl great resilience and agency. ♦

“In Great Grief, Mubanga Kalimamukwento Saw Her Country” appears in The Next Generation Series, an Open Country Mag project profiling rising African writers and curators, edited by Otosirieze. The groundbreaking first issue, featuring 16 voices from nine countries, was released in April 2022.

If you love what you just read, please consider making a PayPal donation to enable us to publish more like it.

Buy Mubanga Kalimamukwento’s books. Open Country Mag may earn an affiliate commission.

- The Mourning Bird

- unmarked graves

- Another Mother Does Not Come When Yours Dies

- Obligations to the Wounded

- The Shipikisha Club

More In-depth Stories from Open Country Mag‘s The Next Generation Series

— JK Anowe, a Confessional Poet, Confronts Himself

— The Prodigious Arrival of Arinze Ifeakandu

— Aiwanose Odafen‘s Duology of Womanhood

— Momtaza Mehri’s Fluid Diasporas

— The Overlapping Realisms of Eloghosa Osunde

— DK Nnuro Finds His Answers

— How Romeo Oriogun Wrested Poetry from Pain

— Suyi Davies Okungbowa Knows What It Takes

— Why Tobi Eyinade Built Rovingheights, Nigeria’s Biggest Bookstore

— Remy Ngamije on Doek! and the New Age of Namibian Literature

— Ebenezer Agu on 20.35 Africa and Curating New Poetry

— In Writing Cameroonian American Experiences, Nana Nkweti Crosses Genres

— Oghenechovwe Donald Ekpeki‘s Curation of African Speculative Fiction

— Logan February on Their Becoming

— The Cheeky Natives Is Letlhogonolo Mogkoroane and Alma-Nalisha Cele‘s Archive of Intentionality

— Cheswayo Mphanza on Intertextual Poetry and Zambia’s Moment

— The Seminal Breakout of Gbenga Adesina

— Keletso Mopai Owns Her Story and Her Voice

— Troy Onyango on Lolwe and Literary Magazine Publishing in Africa

— At Africa in Dialogue, Gaamangwe Joy Mogami Lures Out Storytelling Truths

— Khadija Abdalla Bajaber on Fantasy and the Character of Kenyan Writing

One Response

This a touching and inspiring story . It’s wonderful to see her receiving recognition globally. The story highlights the growing presence of Zambian literature on the world stage.