Lower Manhattan, on some nights, was a spread of book parties, gatherings of writers and editors, publishers and publicists, and booksellers and photographers from the rest of New York City and America. In these exclusive readings spiced with heady wine and set in affluent backyards of patrons of the arts, paths crossed and careers were set.

And so here, eleven years ago, came a bespectacled 34-year-old man. In literary America then, he was an unknown. Not least at a party that had in attendance Salman Rushdie, Francine Prose, and Jay McInerney: properly famed figures. He was a private person, private and intense. He had artistic ambitions but they were on the page, and they weren’t do-or-die. Above all, he had a roving curiosity, a need to know. He was not afraid of deploying it in dialogue, and he was a natural communicator.

He moved from one small cluster to the next, listening for chats of his interests, until, under a magnolia hung with tiny bulbs, he met Jennifer B. McDonald. She told him she had just resumed as assigning editor at The New York Times Book Review and he told her he was a street photographer and doctoral student of art history, studying 16th century Dutch paintings at Columbia. They slipped into a conversation about music and agreed to, someday soon, attend a performance together in Brooklyn.

Surrounded by chatter and cheese, in the midst of people they’d only met through books and news, writers living other writers’ dreams, they stood looking around, a binary of the estranged, uneasy and starstruck. Teju Cole leaned on the tree and sipped his wine. He turned to her. “I feel like a nobody,” he said.

Three years before, in his home country, Nigeria, he’d published a novella, Every Day Is for the Thief, an episodic book whose dimming of the line between fiction and nonfiction, pairing beautifully hewn prose with unassuming photographs of Lagos, quietly opened a new path for the African novel. Then the summer before the party, he completed another fiction manuscript, set right there in New York City, five years after 9/11. It was a novel that braided local and global histories, a book of psychogeography. Its narrator walks around absorbing nature and the stories of strangers, commenting on culture and critical theory, and in his digressions of philosophical reverie the past becomes present. He is watching birds, deciphering classical symphonies on radio, taking in the sounds of the Hudson River. The details accrue beautifully.

Its title, “Open City,” came from the wartime convention of letting an invading army into a city in order to prevent it being bombed or destroyed, to preserve its structure and heritage. It came, too, from his suggestion of an openheartedness to culture, his belief in the idea of literature, of art, as uncontainable.

In Julius, Teju had created a truly kinetic mind, a character intellectually similar to but personally different from himself. A Columbia psychiatry fellow, with a Nigerian father and a German mother, Julius casts a claiming gaze on the world. He fit into the new class of Africans born or resident abroad and wearing their cosmopolitanism: Afropolitans. He is that class’ first major fictional character. In manner, Julius embodies an audacious Americanness that Teju himself, despite being born in the country and having lived eighteen years in it at the time, did not feel he belonged to just yet; a confidence personified, Teju felt, by the then president, Barack Obama, and the Dominican American writer Junot Diaz.

The narrative wasn’t conventional fiction, had no plot, no humour. It was driven by curiosity and connectivity and not conflict. It was obsessed with place and the abstract and not human drama, and so it lay outside ideas of a set Anglophone African literary realist tradition, tied to the fiction philosophy made famous by Chinua Achebe. Although a few African writers had nudged the tradition on varying levels of concept and form—Ghana’s Ayi Kwei Armah, Zimbabwe’s Dambudzo Marechera, the Republic of Congo’s Alain Mabanckou, in translation from the French—Teju knew that most of his Nigerian contemporaries—Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Helon Habila, Chris Abani, Sefi Atta, Uzodinma Iweala—were producing important novels in it.

But he had no qualms being different. His influences were multifarious, substantially non-African and non-Black. He loved Michael Ondaatje, J.M. Coetzee, James Salter, and Michael Tournier as much as he did Wole Soyinka. He appreciated Shakespeare as much as he did Yoruba mythology, James Joyce’s Dubliners as much as he did Kofi Awoonor’s Ewe-sharpened poetry. He thought Penelope Fitzgerald was the perfect novelist. He was fascinated by Joan Didion, John Berger, and V.S. Naipaul, and just after he finished Every Day Is for the Thief, a friend introduced him to W.G. Sebald, whose Rings of Saturn and Austerlitz, in their blurring of the real and the imagined, became a major influence in the early chapters of Open City.

Ultimately, he felt that the traditions of European art, film, music, and philosophy belonged to him as much as they did the next French singer or Swedish actor or Polish painter, and he found as much meaning in them as he did in the sound of Sunny Ade or the paintings of Wangechi Mutu or the bronze sculptures of 14th century Ife. He had also entered photography at the same time he did literature, and he wanted everything he was made of to show in anything he created.

He had written only a third of the manuscript before his then agent, Scott Moyers at the Wylie Agency, sent it off to publishers. It was 2008. At Random House, the editor-at-large and bestselling novelist David Ebershoff fell in love with its “original mind,” its prose moving like a river, and acquired it. He had edited the English translation of Austerlitz and understood what Teju wanted to achieve. Teju’s then publicist Jynne Martin also knew how unique a writer he is, but presenting an unknown, composite African — who’d dared to start his career with exactly the book he wanted to write — was tough. They shifted the release date from spring 2010 to winter 2011.

They marketed the book to “readers of Joseph O’Neill and Zadie Smith,” two dissimilar writers whose conjoining, they hoped, might begin to capture the novel’s breadth. And yet beyond broad thematic strokes — O’Neill’s post-9/11 New York novel Netherland, Smith’s stories of multiracial London — Teju wasn’t like them. He wasn’t like anyone. His expectation was that this second book, like his first, was also not going to have a wide appeal.

But later that year, an excerpt appeared in Tin House and won early readers. Ebershoff asked Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, as the most established contemporary African writer in America, to co-host a luncheon with Random House, to introduce Teju to journalists. She did and it was a success. Teju would hold his own launch night at Greenlight Bookstore in Brooklyn, and, hours later, a party at a Nigerian restaurant called Buka, both attended by over a hundred people.

In February of 2011, when Open City arrived, it received high praise from critics, who lauded him as an interpreter of cosmopolitanism, a leading bicultural voice. A long review in The New Yorker, in which James Wood called it “a beautiful, subtle, and finally, original novel,” set the tone. The Nigerian social critic Ikhide Ikheloa noted it as “a refreshing and eclectic departure” from the suffered tone of the typical immigrant story.

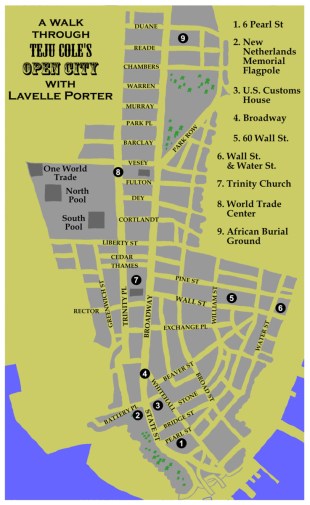

The novel would be shortlisted for the National Book Critics Circle Award and win the Internationaler Literaturpreis, the PEN/Hemingway Award, the New York City Book Award for Fiction, and the Rosenthal Award of the American Academy of Arts. Although it never became a national bestseller, it would be translated into 15 languages, become the subject of extensive academic discourse, and instantly lift its author into the upper reaches of his generation’s originals. It would inspire a collaboration with the jazz pianist and composer Vijay Iyer and parts of his 2015 album Break Stuff. It would have its own fanbase, complete with a literary tour map of its narrator’s walks. Flavorwire would rank him 40th on its list of “New York’s 100 Most Important Living Writers,” and later he would win the Windham Campbell Prize.

“The hardest part of publishing Open City was also the easiest,” Ebershoff, now Vice President and Executive Editor at Hogarth Books and Penguin Random House, told me in early May. “It is not an easy book to pitch. Any attempt to summarize it becomes dissatisfyingly reductive. The language and metaphor are as important as plot and story. Subtext and tone reveal as much as dialogue and action. It wasn’t an easy book to talk about conventionally. On the other hand, once people opened it and began reading, it was easy to convince them of its greatness. So I went around asking people to read the first chapter. I said, ‘Do that and you’ll know.’ Enough people did. After that, it wasn’t particularly hard to publish.”

Ebershoff said that the main reason he wasn’t worried about the novel’s prospects was simply because he loved it so much. “It was precisely because of Teju’s unique perspective. Born in America, raised in Nigeria, steeped in European art, philosophy, and literature, he sees the world, and interprets it, unlike anyone else. I knew many people would feel this way about him and Open City.”

Teju Cole’s difference is a major subplot in a distinctive career. The reporter Matthew Kassel contrasted him with contemporary immigrant writers, like the Indian American Jhumpa Lahiri and the Russian American Gary Shteyngart, who “put questions of identity front and center.” Teju, Kassel notes, “is harder to pin down; he revels in ambiguity.” Former Paris Review editor Philip Gourevitch summed him up: “It’s not like he’s placeless, but he’s creating a new space for himself, a space that isn’t already inhabited by a lot of other writers — other voices.”

It is a meticulously crafted space that now includes Known and Strange Things, a mellifluous cruise through literature, film, music, photography, travel, history, and politics. It is the book that cemented his reputation as a major essayist, for whom, writes The Boston Globe, “there’s almost no subject [he] can’t come at from a startling angle.” Since the three books of prose, Teju has recalibrated his space, with three more books that meld text and images: 2017’s Blind Spot; 2019’s Human Archipelago, a collaboration with the photographer Fazal Sheikh; and, last year, Fernweh.

His books are voyages of curiosity rendered unconstrained. They are versatile lunges of enquiry, Method in manner and seamless in reach. His prime power as a fiction writer is his unity of ideas and character, and his appeal as an essayist is in his marriage of sophistication and accessibility; all blend in his painterly prose. It is an oeuvre in constant reinvention, releasing him, like a canary determined to flex its voice, to bask beyond the boxes that non-white writers are placed in.

Yinka Elujoba, an art critic for The New York Times, discovered Teju’s essays as an undergraduate in Nigeria. “This is really the manner of Cole’s contribution: most of my friends believe that they began to think of the possibilities of literature for us — as Africans — differently after reading him,” Elujoba told me. “The voice, the cadence, the intelligent prose, the concerns, the insight, the allowances he gave himself, everything pointed us towards a new light. Perhaps it was because he straddled two worlds — art and literature — something uncommon for most African writers. Yet he brought the same intense seriousness to both practices.”

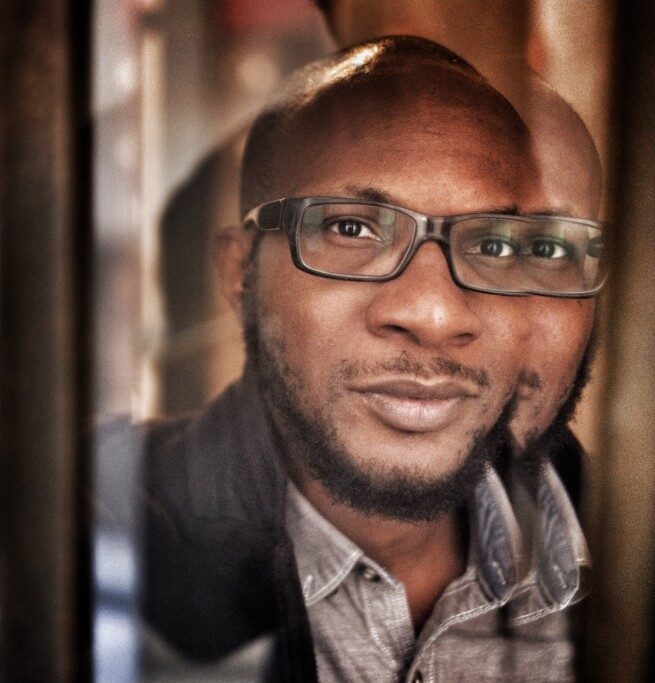

In the middle of March, when Teju gets on a Zoom call with me, he looks as he always does, bald and bearded, collected and reflective, professorial, like he might for his classes at Harvard, where he is the Gore Vidal Professor of the Practice of Creative Writing. He speaks with contemplated warmth, hands moving, and you hear all his cultures, the Nigerianisms, the Americanisms, the gentle meshes in syllables and slang.

On the page and in the world, this is an elusive man; for all his essayistic expressiveness, he shields his history and solitude. “As any migratory bird,” he smiles, “I’m not keen on being captured. One has to protect the space from which the work itself is emerging.”

He takes on the question of literary tradition. “If you talk about Achebe and Things Fall Apart — fair enough, it is set in late 19th century Igboland — what tradition of Igbo novel-writing was he relating to when he wrote it? Because clearly what he’s doing is that he’s reading English novels and he’s making his own thing out of it. He’s figuring out from English novels how to write a novel in English. I’m sure people like D.O. Fagunwa and Duro Ladipo are significant to the work of Wole Soyinka, but the fact of the matter is, what he’s really studying closely is Sophocles, Shakespeare, Shaun O’Casey, W.B. Yeats. Does that make him any less Soyinka? Because you have to express what you are based on what you have learned, the environment that has shaped you.”

“I have never had anxiety about influence,” he contemplates. “I speak Yoruba fluently, I know the music, I know the mythology, I know how I was formed. Some of it is explicit in the work, some of it is implicit.”

The academic Akin Adesokan saw Teju’s approach — “writing about Africa within the context of worldly travels” — in the vein of the pre-slave trade traditions that established Ibn Khaldun, Ibn Battuta, and Leo Africanus as global thinkers. “He wants to do this not on the terms of contemporary understandings of race and culture but on the terms of writing as the mode of fashioning individual sensibilities,” Adesokan wrote in 2013. “This option is not to be construed as avoiding politics, but as conceiving of the political on terms that put the individual first.”

What bothers Teju is the possibility of constriction. “I think I would have been happy with a smaller career as long as I could write my work with the kind of freedom that I’m doing my work,” he says. “What I would not have been happy with is if somebody had said, ‘Ah, the way you make it is to write certain things in certain ways because that’s what we expect of an African Writer.’ But, you know, nobody ever said that to me.”

His parents met in the U.S., in the 1970s, in Kalamazoo, Michigan. His mother worked as a French-language teacher while his father studied for an M.B.A. at Western Michigan University. Teju was born in June, 1975. When he was five months old, his mother took him to Nigeria for the first time. When he turned two, she fully returned to Lagos. Later, his father joined them, working as an export manager for cocoa companies.

For a time, they lived in G.R.A., Ikeja, in a white house cluttered by trees. It was a middleclass family steeped in Yoruba intellectual culture, and he grew up with interest in books. At six, he began to paint, setting up objects in the bedroom with his younger brother and drawing them. At 10, he began to scribble in notebooks, having read Things Fall Apart, Lamb’s Tales from Shakespeare, and an abridged edition of The Adventures of Tom Sawyer. By 11, his eyes became weak and the family doctor recommended that he wear glasses. His family was not surprised: his grandfather, his mother, and his younger brothers had myopia, too.

He was a regular kid living a nerdy life. His father hoped for him to one day go to Silicon Valley or N.A.S.A., but studying for chemistry exams in secondary school, he would often have an art book on his lap. It was the ‘80s, and at school he argued with classmates about politics, the Cold War, always siding with America, rooting for them at the Olympics because Nigeria, as he would later write, was “unlikely to win anything anyway.”

The country was in a slow but sure fall — corruption, decayed structures and education, crime, despair — and the family had a plan: if anything happened, like the war then consuming Liberia, they would drop him off at the American Embassy. He was American and Americans would airlift him out.

When Teju turned 16, his parents pooled their savings so he could study further in the U.S. He was accepted by both W.M.U., his father’s alma mater, and Kalamazoo College, and in the fall of 1992, he went to the former.

“There was no expectation that I will be coming back,” Teju tells me. “As it was back then and as it continues to be now, maybe not as grievously, if you went overseas to study, just because of costs and distance of communication, you were gone for a while.”

America was not Lagos, he found quickly. On his first evening on campus, walking in the cold, it struck him that all the people he loved were 6,000 miles away, and he panicked. For two weeks, he struggled both to understand the accelerated English and to make himself understood. He got student loans and worked at McDonalds. Watching The Phil Donahue Show left him surprised by the American lack of reserve.

He spent one year at W.M.U. before transferring to Kalamazoo College on scholarship, and graduating in 1996 with a B.A. in art history and a minor in pre-med. In the midst of his studies, in 1995, he briefly visited Nigeria. His parents, encouraging of his art dream, were nevertheless puzzled. Art would be just for undergrad, he assured them, and then he would do the befitting thing: study Medicine.

It was at Kalamazoo College, on that small, quiet campus, that Teju’s rabid curiosity grew wings. One session, he returned from a study in Aberdeen, Scotland, and entered the office of one of his art professors, Billie Fischer, and began to ask her about the Dutch baroque painter Johannes Vermeer.

“I remember thinking, ‘Who is this kid from Africa who wants to talk about Vermeer?’” Fischer recounted years later. They became friends and she began inviting him to her house, and they would sit together and watch movies. She had a stack of magazines, copies of The New Yorker arriving weekly, which he spied enviously.

“That was a revelation to me that people lived that way and made the arts the center of their lives,” Teju recalled in a 2011 interview. “Without people like that, my imagination might have remained more parochial.” Later, he said of her: “She was one of these people who gave me the sense that the world did not have to be narrow.”

Teju spent most of his time at the library, reading books unconnected to his courses, and in its basement watching European films. His grades weren’t exceptional but his sense of the world was expanding. It was at this time that he discovered Krzysztof Kieślowski’s Red, a film whose quiet vigour stayed with him, into his writing.

In his apartment, he listened to music. He was getting into jazz and classical music, and on the wall of his dorm room was John Coltrane. Although there was a lot of his parents’ ‘70s soul and late ‘80s-early ‘90s R&B in his childhood, music, until Kalamazoo, had been on the fringe of his life. Now he was listening to Mahler, to Beethoven; to the Malians Ali Farka Touré and Oumou Sangaré; to highlife: Dr. Victor Olaiya. Now he was telling people, “Listen to this, listen to this,” a habit he has retained.

For his senior individualized project, a cell biology research, he went to Harvard Medical School. It was there, in Boston, that he began taking walks, began his habit of wandering and observing, listening to Lauryn Hill, and Mos Def and Talib Kweli’s Black Star. After two years, realizing that medicine was not for him, he finally, fully, turned to the humanities, leaving for the University of London to study African art history at the School of Oriental and African Studies.

In the 13 years that Teju was away from Nigeria, through different jobs as a dishwasher, gardener, cartoonist, haematology researcher, and lecturer, his mind roved the world. He’d become a born-again Christian at 13, but, by 28, he swerved to atheism, a step, he said, that altered his “relationship to the world and ethics.” He would shift once more at 33, outside religion entirely, to an “even keel” relationship to spirituality that allowed him to fully own his “sense of how to move forward in my life.” He defined himself by the interior happenings, and the central moments of his life, he would later say, “have had to do with my relationship to my own being in the world.” In all those years, he was slowly unfurling in self-discovery, and by 2004, a year after moving beyond atheism, while in London, his mind began to settle, on writing and on photography.

When it came to words on the page, he was drawn as much to style as to substance. He hoped to one day write a “free book” like Coetzee’s Elizabeth Costello. He looked to writers who, he told Guernica, “don’t take language as a boring, settled thing” and “deliver it with corresponding freshness on the page.”

Although he didn’t write serious poetry, his deepest happiness came reading verses. He liked poetry’s tightness, its “intensely localized effect.” His touchstones: Tomas Tranströmer, Wisława Szymborska, George Seferis, Anne Carson, Charles Simic, Sharon Olds, and generally, he told BOMB, “anyone who has found a way to sidestep conventional syntax,” whose prose “contains the elusive and far-fetched.”

In honing his style, his training in art came in handy, the necessitation of contemplation, of unrushed uncovering. He was still learning to shoot with a film camera, and that visual quality seeped in. He thought that if he were a movie director, he’d use slow-motion too much.

He used that slow, steady hand to build the fabric of his writing: mood. He was heeding the Estonian composer Arvo Pärt: “It is enough if one note is played beautifully.” All he needed was to create a mood, sustain a space in which, as he told Guernica, “other things might happen to the reader.”

He was not hung up trying to read most of the 19th and 20th century classics. So fixated was he on the inner workings of literature that he didn’t send out many submissions as his writer friends were doing. It was only when he felt he’d arrived at a way of making sentences that was true to him — it was only then that he sought a subject.

When Teju Cole returned to Lagos in late 2005, Nigeria was six years into civilian rule and relative open expression, and the national metamorphosis was intriguing for someone who had been away for a decade. “There was something about that trip that struck me very, very differently,” he tells me. “I felt that I had arrived not in a different Nigeria but in a Nigeria that I understood differently. I had sort of come of age in a certain way that now I was looking at it not just as ‘Oh, I’m going back home,’ but ‘I’m going to a place that calls for annotation but also for interpretation.’”

Culture was returning in style: homes were filled with Nollywood CDs, shops and vehicles spilled Afropop hits, and in museums, curators were again treating history and art with seriousness. Lagos, Africa’s biggest and most populous metropolitan area, was flourishing.

To describe what he saw, Teju took to a rising medium: blogging. From January 2006, he blogged about where he went: parks, galleries, agency offices; the people he met: artists, hustlers, passengers; how they behaved: hopefully, cynically, street smartly; what he thought; what it might all mean. Blogging eight hours a day, producing a chapter per day, the project took him a month to finish.

His inclusion of black-and-white images came naturally, from his interest in photography and his training as an art historian. He’d also read Ondaatje’s fiction debut, The Collected Works of Billy the Kid, and two nonfiction books, Orhan Pamuk’s Istanbul: Memories and the City and Roland Barthes’ Camera Lucida, which all embedded images in text.

He did not necessarily set out to capture Lagos, its visceral, intense, incessant multivocality, in a way that no one else had; he already believed that “the best novel of Lagos” was the discography of Fela Kuti, who, he wrote, “earthed the lightning of our contemporary life,” weaving micro struggles in a way that is “very hard to do in literature.” He thought Fela to be Nigeria’s greatest genius. The incandescent anger, the savage humour of Beasts of No Nation/ODOO (Overtake Don Overtake Overtake), the pain of the title song—it had, he felt, a blazing beauty, like “a house on fire.” He preferred nuance but also knew when the artistic response needed to be raw, so he did not flinch from showing a lynching of a thief. The title, “Every Day Is for the Thief,” came from a Yoruba proverb: Every day is for the thief, but one day is for the owner.

A few hundred people read it. Weeks on, he deleted it. Months on, he received an enquiry from a new publishing press, Cassava Republic. They edited it, replacing Teju the original narrator with a persona of equal eloquence who’d been away for 15 years, and, with that longer absence, now simmered with disillusioned love for a country that should be doing better. In 2007, Every Day Is for the Thief was published as a 130-page novella.

It was in writing the book that Teju decided, like Berger, to straddle fiction and nonfiction, for his fiction to read realistically and his nonfiction to read novelistically. “I think that what we care about, finally, is whether an author can create a world — a sensitively and convincingly evoked world — that we want to inhabit,” he later told Tin House. For some of the earliest novelists — Miguel de Cervantes, François Rabelais, Robert Burton, Daniel Defoe — the demarcation, he saw, wasn’t a rule.

Teju tells me that he categorized Every Day as fiction because it would give him “a clearer shape.” “I think any work of writing, particularly a work of fiction, is coherent based on certain simplifications that you make,” he says. “My own feelings were sort of all over the place, it’s positive, it’s negative. By making it fictional, I was able to focus the emotional temperature of the work.”

He was also particular in its intended effect. “If I was just gonna write a pure memoir of my experience of that time, maybe there would be less fury, maybe I could talk more about family. There were good times, there were people I hung out with, I also had fun. But I wanted to register that shock of a place that seemed mired in circumstances it could not quite escape. And write about what that feels like from the perspective of someone who knows it very well but has not seen it in a while. The ability to look at the familiar with new eyes.”

It was also a reconciliation of his childhood and teenage years with the world-weary thinker he had become. “As a child you don’t really know where you live, you just live it. As an adult, you begin to interpret the structures, you begin to write down what you see, you begin to interpret the meaning of what you’re looking at.”

The arrangement of Every Day gave him deep personal satisfaction. But there was more he wanted to do, and he needed a larger canvas to figure it out.

New York City — its energy, its crossing of cultures, their variegated histories, the discoveries they afforded — gripped Teju Cole on his first coming, back in 2000, when he was transitioning from medicine to art, to enroll at Columbia. The city fascinated him. Vaguely, he began to think about making something, but didn’t know where to begin, didn’t know how.

On September 11, 2001, the Twin Towers fell, and the city and America were plunged into anguish. The force of the terrorist attacks broke open a portal for him, and he began talking to people, in cafes, at concerts, on planes, and he was surprised that they were opening up, sharing what to them were small, insignificant details of their lives, but in which he could see something clear: a failure of mourning. That, he decided, was what he could show, something he hadn’t seen much of in the reportage and fiction on the tragedy.

He believed that the best way to write about catastrophe was to write allusively, about other things, to let the trauma show in shades. The writing must intimate distance and he preferred to fill that vagueness with music, with art. He saw truth in Leo Tolstoy’s warning that events shouldn’t be written about until ten years later, and yet he did just that.

Earlier in London, at the S.O.A.S., he’d written down the first words, five pages of Mad Libs. But in New York City now, he had a title, clear sentences, cumulative observations, relying on clarity to convey the narrative’s energy. He agreed with Didion saying she wouldn’t know what to think until she wrote it down. So he did not tell himself that he was writing a “novel.” It wasn’t his intention, and if it were, he would have over-obsessed, over-sketched, and over-determined its structure to the point of frustration. Instead, he took it patiently, random thought after random thought, seeking flow.

It was another year later, in late 2006, on the day of the New York Marathon, a day he didn’t take a walk, that he really began to write: and on that day, in the beginning of the book, Julius takes a walk, setting out from Morningside Heights, where Teju lived, overlooking the streets full of runners and watchers.

The first character he created was not Julius but Julianne, his German mother, whom those Mad Libs were about, who is estranged from both her own mother and her son. Teju named her after his grandmother and made up a biography for her, most of which he didn’t use in the book. Then came Julius, and a conversation he has with an older man, who became Professor Saito, his Japanese mentor-figure. Once he had the two men, the story began to open up, one sentence asking for another; he was feeling an internal pressure and the prose flowed; it was, he would later say, “like a fever dream.”

Although the writing of the two books overlapped — he began Every Day in January 2006 and, as a way to procrastinate edits for it, Open City in November of that year — his ideas for the latter were a significant leap. In its final stages, he looked to maximize the possibilities of the novel, aware that there are internal conditions that only the form could achieve. He wanted to explore stream-of-consciousness without falling into tedium and tedium itself without becoming tedious. He thought of Naipaul’s The Enigma of Arrival and James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time, both written in a strong first-person voice, thriving in gaps between reportage, essay, and innovation.

He also expanded the external, presenting intellectual life as he did in Every Day, with characters going to bookshops, museums, having cultural experiences with no plot conflict. In threading Julius’ thoughts, he avoided heavy research so the book wouldn’t read like Wikipedia. He wanted it to read naturally, without quotation marks, a stream of musings.

He meant for some of the scenes to read the way art is meant to be seen: yielding more on rereading. The intent was aesthetic and psychologic. He was thinking of Pieter Bruegel the Elder and his Renaissance landscapes. Like the Old Master European paintings, he wanted Julius’ human encounters to reveal more afterwards.

His devotion grew at the expense of his studies, and his wife, Karen, became concerned again — given how he’d eloped with Every Day. She would return from work and he would tell her, “I did a lot of work today,” and she would ask, “On your dissertation?” It became a running joke among his friends.

He missed his submission deadline from Random House. In the summer of 2009, in his new apartment in Sunset Park, Brooklyn, he wrote the last chapters, 21, 19, and 20, in that order. The day he finished, he went out to a Mexican neighbourhood, into a restaurant he’d never been to, and ordered enough food for four people. He ate, smiling at strangers. And then he went home and took a shower.

Fifty pages of Open City are set in Brussels, the Belgian capital. Teju planned this detour to extend an irony: here is a psychiatrist who talks about everything but nothing about what happened with his mother, who travels to another continent to locate his grandmother but doesn’t make a concentrated effort to find her. The arc also best exemplifies how the novel functions on doubles. For New York City, there is Brussels: a city that, during World War II, was actually an “open city,” surrendered to Nazi German forces in 1940. And in Brussels, for Julius, there is the young Moroccan man Farouq: as liberal, as sensitive to history, but possessing greater rigor, more militant in his diagnoses, more idealist.

In Open City, there is an abundance of the unstated, the observed but uncommented upon, and it builds Julius’ complications. He may engage robust logic on global systems of oppression, but he wrings away from racial attachment, from almost every encounter with a fellow Black or African, all “people who tried to lay claims on me.” His need to be differentiated feels cryptic and colonialist: he would take the heritage but not the baggage — a posture that invites fresh problematization in the age of Black Lives Matter. (The novel is set during the Bush Years, but Teju, writing most of it later, has called it an “Obama Book.”)

But there is also the author’s own contrarianism. This, after all, is a book about the old bleeding back into the new, a book, he has said, about “a new kind of American reality, one that takes diversity for granted,” that “doesn’t celebrate diversity, actually, it just says: this is how we live now.” To take diversity for granted, to honestly presume the naturalness of difference, is to dare give full life to a Julius, a character fleeing racial attachment, against convention.

But nowhere is the unstated, the uncommented upon, more obvious, and troubling, than in Julius’ attitudes to gender. Near the book’s end, an acquaintance, Moji, accuses him of raping her when they were teenagers. “I don’t think you’ve changed at all, Julius,” Moji says. “Things don’t go away because you choose to forget them.” She tries to hold him accountable: “But will you say something now? Will you say something?” Julius says nothing, he simply shifts attention to the beauty of morning light on the Hudson, and a story Albert Camus told about Friedrich Nietzsche.

In the cerebral shimmer of the narration, the scene is a chilling irruption. It proved divisive with critics and readers, most of whom thought it was striking, the rest of whom felt it was unsatisfyingly unresolved, or ill-tailored into the story’s vast scope, or just wouldn’t want their attachment to a fine intellectual mind to be so troubled.

“What’s interesting to me is we all know, unfortunately, very many women who have been assaulted, but we rarely know men who have committed assault,” Teju says. “We either don’t know or we don’t wanna know. We don’t want to acknowledge the extent to which we know. And that is why I put that incident so late in the book, because I wanted to ‘normalize’ Julius as intelligent, intellectual, curious, likeable/not likeable. Life is not like, ‘Oh, he’s this wonderful character and then there’s this shock.’ It’s more like, ‘He’s this person who really does feel like a person.’ If he doesn’t come across as a real person, then the events of Chapter 20 don’t have the force that I intend them to have. Without that ending, it would have been a nice intellectual tour, but then came the knife.”

He wrote Moji’s voice to supplant Julius’ in that moment, so that even though he is the narrator, she surges past him in spite of his hesitation and editing. It reads as if, for the first time, another voice takes over the narration — which is significant considering that Julius has encountered people as forceful as Farouq.

“Ten years on I feel great about what I went for in that book,” Teju says with relief. “I did what I wanted to do. And I would humbly submit that it holds up.” (I do not point out that his writing year, 2006, would go down as the start of the Me Too Movement.)

More women in Julius’ life face his hesitation to search himself. His girlfriend, Nadege, sometimes registers as secondary in his thoughts; for a lover he never passes through a lens of desire, he is particular in portraying her “uneven walk. . . the way she moved her body in compensation for a malformation.” The sex he has with a Czech woman, for all the words spent on it, feels plastic, lacking in soul. The only women he seems to really see — Dr. Annette Mailotte, his grandmother (whom, he surmises, might have been raped or sexually assaulted by the invading Russians in 1945) — are women on the same footing, intellectual or familial, with him. It is, Teju agrees, “a very wounded relationality to women.”

It contrasts with what feels like a mental gravitation towards men. Julius describes men, noting their nuances, like he does Farouq, and like he does Professor Saito, the person he is fondest of, who happens to be gay. When I first read Open City six years ago, I received Julius’ attitudes to gender, with his aversion to looking inward, as perhaps hiding a queer history.

“I would say that Julius is queer-friendly, it doesn’t strike me that he is queer, you know,” Teju replies. “I don’t think it’s illegitimate as a view, but we see him, he has a girlfriend, there’s a woman he assaults, I think there’s definitely a kind of heterosexual toxic masculinity going on there.”

He admits, “The writer can be very intentional but there might be more interpretative possibilities than intended. I read a paper where someone made an elaborate case that Julius, through his mother, is actually Jewish. This scholar proves the case with clues throughout the book. I’m like, that’s interesting, really interesting, also not impossible, but I did not sit down to write Julius as secretly Jewish, as secretly queer.”

The way that Teju wrote Julius, sketching so close to his own life, coloured how some readers perceived him the author. He received letters presuming he was Julius, which did not offend him. “I think it’s an interesting tension,” he said in 2015. “[It] says something about the expectations we have about what a book is supposed to do. Maybe to a certain extent, this particular book is stymieing those expectations a little bit.”

“One big difference between my characters and I,” he has said, “is that I usually have a pretty dark and ironic sense of humor.”

It was after Open City that Teju’s gusts of experimental energy spilled beyond formal writing, and with it that sense of humour withheld in his fiction. The recreational context of Twitter made it possible. His “Small Fates,” a series of over a thousand micro stories culled from Nigerian news, was an influential step into social media intellectualism. It was based on the fait divers, a centuries-old practice in French journalism.

“Even if one does not believe in ghosts, 2,700 of them continue to draw salaries from the Imo State payroll,” reads one. Another: “Knowledge is power. He graduated in business administration in Calabar, and Charles Okon has since administered sixteen armed robberies.” “Small Fates” helped inspire the Twitter Fiction Festival.

Another series, “Seven Short Stories About Drones,” from 2013, imagined lives for victims of American drone strikes, each tweet starting like a classic novel. “Mrs Dalloway said she would buy the flowers herself. Pity. A signature strike leveled the florist’s.” “Okonkwo was well known throughout the nine villages and even beyond. His torso was found, not his head.” By tying famous books to everyday stories of faceless people, he was reframing distanced tragedies, bridging art and app, the classic and the contemporary, canonical cruxes and disownable deaths, and universalizing the planned happenstance of militarist violence.

The Indian writer Amitava Kumar once called him “one of the great tweeters of our time,” hailing his “exercise [of] poetic instincts.” His social media use made headlines. Twitter, he has said, is “the real stream of consciousness.” He told The New Inquiry that he used it to “bring the literature to [people] right where they are.” He compared the app to an “African city” and rejected the idea that his work on social media was less important than his books; our rewarding of literary production, he believes, will eventually exceed just “books” as we know them.

His Twitter experimentation peaked with his release of a micro story on the app. He retweeted lines sent to friends and a 33-tweet story unfolded on his timeline, titled “Hafiz.” It was a new level in Twitter Literature, harnessing the app’s responsive nature.

Later that year, he would give a lecture at Twitter’s Headquarters, and then he would leave the app, stunning his over 250,000 followers.

Good time for that Twitter break. Ever yrs, &c.

— Teju Cole (@tejucole) July 15, 2014

He never understood Snapchat, couldn’t connect with Vine, and finally settled on Instagram, hoping to find a new mode of pictorial criticism, of image sequences as essays. On Facebook, he remains expressive, regularly sharing Spotify playlists, 104 of them.

“If somebody tells you that a five thousand-word essay in the New York Review of Books is the only way of being serious, they’re lying to you,” he once said. The irony must have eluded him: Who but Teju Cole, whose tribute to the photographer Marie Cosnidas became the longest sentence published in The New York Times, better represents the perception of Long/Important essays in highbrow publications as a way of seriousness?

There is a very public attraction to Teju Cole’s worldly reasoning, so that some of his essays appeared as intellectual events, dissected on social media and blogs. “The White Savior Industrial Complex,” a viral one, grew from his tweets criticizing the viral KONY 2012 video, the “banal sentimentality” of Western humanitarianism in Third World countries. “Black Body,” his rereading of Baldwin’s 1953 essay “A Stranger in the Village,” and claiming as his “heritage” European artistic traditions, spawned multiple analyses.

One of his most important is “A Reader’s War,” his criticism of Obama’s drone strikes in the Middle East, which set up his political commitments on a tense slope, far away from the distanced bubble of his narrators. It put him in a line of fire in mainstream liberal American circles, and, as a new writer, he hedged.

Three years later, though, there was no hedging when PEN America announced that it was awarding the French satirical newspaper Charlie Hebdo, which has a history of hitting political and religious leaders, with its PEN/Toni and James C. Goodale Freedom of Expression Courage Award, following the Al-Qaeda terrorist attack that killed 12 and injured 11 of its staff. Two days after the massacre, Teju had responded with an essay, “Unmournable Bodies,” which received some pushback.

He led a dissent of six writers — Ondaatje, Francine Prose, Peter Carey, Rachel Kushner, and Taiye Selasi, all scheduled to be table hosts at the PEN event. They dissociated themselves from the awarding on grounds that “PEN is not simply conveying support for freedom of expression, but also valorizing selectively offensive material . . . that intensifies the anti-Islamic, anti-Maghreb, anti-Arab sentiments already prevalent in the Western world.”

Alliances broke. Salman Rushdie, 30 years after his fatwa, tweeted: “The award will be given. PEN is holding firm. Just 6 pussies. Six Authors in Search of a bit of Character.” He later called them “fellow travelers” of “fanatical Islam.” But more PEN members were already distancing themselves and the number of signatories to the letter grew to 242. The event went ahead. (Last year, on the eve of the trial of the terrorists, Charlie Hebdo reprinted the cartoons.)

But where Teju’s disbelief in American exceptionalism prompts his activist tendencies, his attitude to Nigerian dysfunction is conventional: he puts the criticism in his books, speaks on panels and, almost as if it were futile, avoids table-shaking essays.

A few Nigerian critics, riled by his depiction of Lagos in Every Day Is for the Thief, accused him of Afro-pessimism. He dismissed the suggestion as “just a little bit empty, sometimes”; if people are really suffering, why paint a rosy picture? His home country, he told BOMB, “haunts me in terms of being a space of unfinished histories.” I ask him if these histories of “squander,” as he put it, are why he doesn’t publicly comment on Nigerian issues.

“Nigeria is in a tough place right now,” Teju says, his tone resigned. “There are too many forces arrayed against us: violence, mismanagement. We used to be able to simplify them into, ‘Oh, it’s just corruption,’ or ‘Oh, it’s just the military.’ But now it really feels like — this Boko Haram thing, hugely intractable, but then the Herdsmen thing is a huge one as well, and then the separatist movements that are coming to the fore every day, and then on top of that we have incommunicativeness. It’s a powder keg. More enlightened leadership would help, and a real commitment to reducing inequality. It’s one thing to be a poor country, it’s another thing to be a poor country that has so many rich people, and yet it’s another thing to be a poor country that has so many rich people intent on demonstrating their wealth. I wouldn’t say we need better political education, but we need for the people who have the political education to have more of a platform so that their voices are heard.”

The class inequality disturbs him the most. “Boys can go out for a drink, and by the time they’ve ordered one round, that already pays the monthly salary of the guy who’s opening the door for them. That’s normal in Nigeria, but that kind of normalcy — that’s what revolutions come out of.”

He understands the pressure building up inside the system. “There was almost like a valve release for that during End SARS. It’s part of a larger pattern of being disregarded. People are not stupid, you know. The people protesting know that they are just as smart and as hardworking as the people living large. It is possible to envision a kind of future that isn’t dependent on having a permanent underclass. I don’t know how we are going to get there. We need a vision that can speak to Sabo, Áseése, Makoko, to every neighbourhood in every city in this country that has the wealthy cheek by jaw with the impoverished. When I got to V.I., right next to the hotel, there were people sleeping under aluminum sheets. We need a vision of a society that can somehow include the least among us. We are all in this together.”

Teju moves as if to lean close to the camera. What he sees is a foreclosure of the horizon of imagination, how news of Nigerian international firsts are an optical illusion. “It’s like a version of Black People Magic,” he says. “That’s not gonna save us. I don’t give a damn what Nigerian becomes a billionaire, but we are under-educating other people’s children. There’s a naivety among smart young Nigerians who think the private accumulation of wealth is the only horizon of possibility. Smart young Nigerians seem to think that neoliberalism is our way forward. It’s not. Our salvation does not lie with the global neoliberal network, it does not lie with Goldman Sachs, it does not lie with hedge funds, it does not lie with Silicon Valley. If you have a buildup of wealth that goes to a tiny percentage of a country — history never fails as far as this goes: that system will collapse and it will be very messy.”

Last year, in his home in Cambridge, Massachusetts, Teju was in deep thought. Donald Trump was president. The coronavirus was decimating the world. George Floyd was dead and Black Lives Matter protests had swept the country. In faraway Nigeria, the End SARS protests had begun, thousands of young people demanding answers on the streets and on social media. It was a charged, changed world, and he might have pondered if our regular ways of seeing and feeling were still enough.

One sunlit evening in October, weeks before the election of Joe Biden as U.S. president, he carried his camera into his kitchen and began to photograph the counter. A glass of ice. A red knife. A bottle of gold wine. Bowls of blue. Slices of yellow lemon. The dark table providing a balance of hues. Every day, for five weeks, he did this, borrowing from the still life tradition of Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin, Paul Cézanne, Laura Letinsky, and Jan Groover. But unlike them, he left the placing of the objects to chance. It might have been his way of reassembling the staled energies of the lockdown.

A friend once told him: “In almost every single one of your photos, there is something wrong.” And he, who has spent more time in the last 10 years taking pictures than writing, took it as a compliment, a target, for his work to “be made of hopefully poignant fragments that I then seek to reunite with each other.”

This month, the sequence of 60 kitchen photos will appear in his fourth photo book, Golden Apple of the Sun, accompanied by a 15,000-word text on hunger, fasting, poetry, and the history of photography, both interspersed with a handwritten cookbook from 18th-century Cambridge. In a blurb, the photographer Stephen Shore writes: “Many artists have felt the lure of juxtaposing photographs and text, but few have succeeded as well as Teju Cole.”

(Sharpness did not come to his eyes with the willful work that it did his prose. Just after Open City came out, he suffered a Big Blind Spot syndrome. The book has a scene on the mechanics of blindness; it was ironical, his life imitating his art. As he struggled down the street that afternoon, the sun felt like a hallucination. With surgery, he recovered his sight, but also acquired a new appreciation of light, a fresher way of seeing in which the ordinary looked glorious. It was a turning point in his photography, lending it mystery and meditation.)

Teju once said that the “authentic truth” of photography is “available only in language, as practiced in narration.” While his writing has been influenced by images — like the Black Lives Matter protesters’ “visual language of the comic-book superhero” — he understood that the logic of writing differs from that of imaging. The annotations to his photos are often not about the images — he prefers his images to hold their own, to be more than illustration for the text.

When he began working with Fazal Sheikh on Human Archipelago, poring through Sheikh’s images of landscapes and people forced out of their homes and lands by political and environmental crises, he considered the global rise of xenophobia, and cooled his words through ideals of compassion and courage. Aside Human Archipelago, all photos in his books are taken by him.

But it was in the process of composing Fernweh, his most recent book — a convergence of the histories of photography, tourism, and the fragility of landscapes, with images taken across six years of visiting Switzerland — that he finally felt that his photography and his writing were coming from the same place, that still but searching tenor. Part of it came from writing his Times monthly column, “On Photography” (a finalist for the National Magazine Award in 2016).

“Fernweh” is a German word for the opposite of homesickness; it translates to “farsickness,” a desire to stay away, which took on significance as the book came out in a world of COVID-19 restrictions. He chose Switzerland for its clean beauty, but also because he did not, like many young American photographers, want to make a generic photobook about Brazil or Mexico or India. He believed in ethical travelling, in imagining what real life is like for people living anywhere he went. So he, an African born in America, went to Europe, to its buttered centre of white privilege, with a camera and an intent to discover, an eagerness to exercise expertise, like Europeans once did in Africa and America.

He was taking in Joachim Brohm’s patterns of composition at the time, and he had begun to prefer images with what he calls “a very slow surface,” the kind that elicited a “Hmmm” rather than a “Wow,” the kind that fills his Instagram, the kind he knows is often categorized as “boring.” He sequenced Fernweh with the influence of Dayanita Singh’s Museum of Chance and Rinko Kawauchi’s Illuminance, books that, he felt, lured stories out of fragments.

But this new one, Golden Apple of the Sun, builds on the texture of his first photo book, Blind Spot, in which his travels for literary events — to Zurich, Tripoli, Lagos, Beirut, Seoul, São Paulo, Berlin, Ubud — are captured in 150 “tourist’s pictures,” each annotated by brief luminous prose. It is the book he considers his most original work. (“A real contribution. There is, like, literally no other text that is like that.”)

He called it “Blind Spot” because it is about all the things we miss as we go through life. But he wanted to end the book with a double vision, so the last photo in it, taken in Brazzaville, is accompanied by a short text that begins: Darkness is not empty. It is information at rest. It was him, a writer whose books always begin in the middle, seeking a generative ending.

“It’s different from Blind Spot but it has as much text as Blind Spot,” he says of Golden Apple, and for the first time I see how it looks for Teju Cole to be stirred, a quiet charge in his spectacled eyes, on his face, his gesticulating hands. “I’m very excited about that. Nobody else needs to be excited. I think it’s one of the most exciting, most interesting, and original things I’d ever done. And for me, there’s no other work by anybody else I can compare it to. It’s something that my experience has brought me to as a form, to say, ‘Look at this, look.’”

For years, critics have hinted that he is on a search. Reviewing Open City, Miguel Syjuco wrote: “Cole suggests that we re-examine, as perhaps limited and parochial, the idea of the Great Fill-in-the-Nation Novel. Instead, we can look again at the notion of what Goethe called Weltliteratur. This book may not be the Great World Novel, but it points to such a work’s possibility and importance. Judging from his performance here, Cole may eventually be the one to write it.”

I ask Teju about his deliberate movement from novella to novel to essay to photobook, all drawing from poetry, if this cross-pollination is him testing forms to know their capabilities, if he is feeling towards an ultimate, composite work that transcends genre and delineates the world uniquely, with the sensorily sharp temperament he has used to create fiction that feels nonfictional and photobooks that are novelistic: not a Great World Novel now but a Great World Book. I ask him if he had this is in mind when he said that “The central thing motivating my photography and by extension my writing is the idea that there was a mythical pre-history of humanity when everything was intact.” Is this the goal then, realizing that pre-history in a modulated form, as a kind of super-history?

Teju is quiet, looking at the corner of the screen. “I have been very gratified by the work I’ve done, because I think freedom is important, but I think the work I’d done since then indicate my relationship with this particular ambition of writing ‘the great novel’ —”

“Book,” I say. “The Great Book.”

“The Great Book,” he repeats, an unasked question. “Great, by what measure? It seems to suggest something that has to do with scale, size, as a deposit of intent. You know, I think it’s possible that that’s also participating in a kind of masculinist view of what literature can be or what it can do, that real power comes from size.”

I clarify that I mean a scale of quality, not size. He nods. “The thing is, when you’re approaching form, there are certain things you need to say, and the process of saying what you have to say will let you know what the ideal form is. I’m not in a hurry.” He stresses hurry, a slight drag, and he breathes. “What interests me is to do the work and to do it well. If I was listening to that, people wanting me to write another novel, I would never have made Blind Spot.”

The year Blind Spot came out, 2017, he presented a solo performance piece at the Performa Biennial, an audiovisual response to the Trump Age titled Black Paper. This October, his second essay collection comes out with the same name, subtitled Writing in a Dark Time. The photos in Black Paper first appeared in a 2016 solo exhibition in Milan titled Punto d’ombra. In 2019, he held his first major curatorial show at the Museum of Contemporary Photography, Chicago; the project, about freedom and chaos in contemporary America, took its name from the African American freedom song “Go Down Moses.” For years, he was developing a nonfiction narrative about Lagos, titled Radio Lagos. It was research for it that led to “Small Fates” on Twitter.

Now that he is working on that second novel, he prizes freedom and treasures brevity. “Rather than thinking of myself as making this big, powerful, influential book — no, maybe what I would do from now on is just chapbooks. Maybe I’ll just make 12-page books. The point is to be grateful for the freedom of doing work, and to follow the voice and make the work. As the artist you’re thinking of the container and what you’re putting into the container, but sometimes you’re also creating that container. It’s a journey, you don’t know where this is gonna take you. Only in retrospect does it seem like, ‘Ah, that’s obvious,’ because now it exists in the world.”

His body of work is, he says, “a vision of the world, a vision of a certain kind of experience that involves being raised in Africa’s biggest city, being raised in a Yoruba family, coming into the U.S. and studying here, the opportunity to have visited 45 different countries, to have a certain literary sensibility, to have certain interests in music and in art, to have certain political commitments that have to do with equality of persons, and then just to have a certain personality that is my personality because each person has their own. I am committed to a kind of artistic freedom that has led to this body of work.”

He is a disciple of artistic stubbornness. “We need to also have a relationship with a body of established work,” he says. “Excessive originality means you’re kind of, like, a quack, right? And yet having understood the body of work that is out there in the world, the forebears, the masters — at the end of the day when you’ve read your Toni Morrison, or whomever you’re reading, then you have to decide your part in this. And Toni Morrison got where she got by reading Richard Wright, William Faulkner, but at some point, you say, ‘Okay, what does Toni Morrison sound like?’ and she had to be stubborn about it.”

When his agent sent out the unfinished draft of Open City and editors began to indicate interest, Teju feared the book would be deformed, would defer to someone else’s idea. David Ebershoff wanted him to think about plot, but not at the expense of his authorial vision. Editing Every Day Is for the Thief, Ebershoff saw him as reaching for a similar thing as Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. (When Every Day came out in the U.S. and the U.K. in 2014, seven years after it did in Nigeria, Western critics received it as “an epilogue” to Open City, not as a standalone precedent but as a confirmation of reputation, another offering after tragedy, dealing with post-military rule Nigeria as Open City does with 9/11.)

Ten years on, Ebershoff, who also edited Known and Strange Things, looks back with fulfilment. “His journey doesn’t surprise me,” he told me. “I love how he doesn’t let any one genre define or limit him. Whatever he’s working on, it’s always unmistakably Teju.”

Ebershoff sees writers working in the wake of Open City. “Ben Lerner and Rachel Cusk, both of whom are superb, are two examples. I’m now editing the debut novel of New Yorker writer Vinson Cunningham, which is called Consider the Years. He and I have talked about Open City and its powers.” Cunningham’s novel was pitched to him as “a meditative book in the tradition of Teju Cole.”

Over the years, Teju’s work has gone further, garnering as ardent readers the very writers he looked up to — Jan Morris, Derek Walcott, Soyinka, Claudia Rankine, people he sees as “mountains in my literary imagination” — some of whose artistic processes he traces with fidelity in Known and Strange Things. (Like the rest of his books, the collection takes its name from a pre-existing idea: Seamus Heaney’s poem “Postscript”: “A hurry through which known and strange things pass.”) He receives this with gratitude and faint alarm.

He’d met Philip Roth, and when the man died, he was invited to his funeral. As he stood by the graveside, watching the coffin going under earth, an old lady approached him. “I’m so glad you came,” she told him. “Just before Philip died, the last time I saw him, he wanted to discuss your essay about James Baldwin.”

As she spoke, he listened. The service was over, people had moved to the reception, and they were at the graveside, alone, and he was thinking of his life, the work he put in to get there.

Teju moves in his seat now, as if in anticipation. “Listen,” he says to me, “what I tell students: you can have the talent, you can have the desire, but if you don’t have the fire in the belly to make the vision come through, to bring it forth, you’re not gonna last in that game. There has to be a deep, inside stubbornness. I know you know what I mean.”

Teju Cole is staring upwards again. Our interview, scheduled for 45 minutes, has passed the hour and 15-minute mark, and he begins to respond to a question I didn’t ask, a question he has been asked all through his career: the question of audience. “It’s not an unimportant one, but it’s not as simple as people make it out to be,” he says. “I think people who are not deeply invested in literature or who have not thought carefully about it can sometimes function in a very cliched way of ‘Are you writing for white people?’”

He believes that we write for our best readers. “Like me, you went to school in Nigeria: Aba, secondary school; Nsukka, university. And when you read Open City it made sense to you. You are the target audience. It’s because you felt the work was respecting your intelligence, to put it very simply. And that has nothing to do with white or black, with European influence or whatever. When people read my work, no matter where they may be, if it’s for them, it’s really for them. And I would say the absolutely crucial part of the population I’m writing for is young Nigerians. There’s nothing I’ve written that I’ve not had a young Nigerian say to me, ‘Ah, that one really entered, it was like you entered my head and helped me understand something.’”

His tone falls, tired. “But that’s not the presumption that is made, because we’ve been encouraged to sort of caricature ourselves into ‘If it’s not set in a Yoruba village, is it still authentically African?’ Really, are we still discussing this? In the 1920s, our forebears were publishing newspapers, practicing law, arguing against the colonialists, they were studying classics, they had a big sense of the world—more than a 100 years ago and there was a large population of them. They were reading poetries of all kinds, there were jazz orchestras in Lagos. And a 100 years later, we are supposed to pretend as if we are sealed off like some holy kingdom of uninfluenceablity?”

His work represents “a kind of intellectual internationalism that young Africans take for granted in their lives and that they often don’t see reflected,” he notes. “White people always think the world belongs to them, they can be interested in anything, they can read anything and bring it all in, and I don’t think young Africans see that model for them often enough, by the writers that are ahead of them.”

Fourteen years ago, in 2007, when the novelist and art critic Emmanuel Iduma first found Every Day Is for the Thief on a bookshop shelf, he was still 18, an undergraduate at Obafemi Awolowo University, Ife. It was his first time seeing fiction by a Nigerian that incorporated photographs, and the writing itself, he felt, was “nonpareil.” Five years on, when he began studying for an MFA in art criticism and writing, he looked to Teju Cole.

“His example made me feel that my own work was possible,” Iduma told me. “His ideas are never just the sum of their parts, but each part a world entire.” In his debut novel Farad, the influence is obvious. For his second book, a travelogue, A Stranger’s Pose, Teju wrote the foreword.

The novelist Ayobami Adebayo also discovered Teju’s work at the same time as Iduma. “What continues to mean the most to me is how his work yields more insights upon re-engagement,” she told me. “Returning to Everyday Is for the Thief recently, I was transfixed by how riveting its characters are even when observed in passing. Especially Lagos, evoked with such poignant vignettes that it comes into sharp focus, vivid and textured, as though painted.”

Their acquaintance, Iduma said, “highlighted for me his kindness, and how, even if I thought of him as peerless, he considered my thinking deserving of consideration alongside his. Though assured of his path in the world, he continues to make way for all who aspire to creative freedom of every kind.”

That generosity comes through in a fictional letter that Teju published online in 2010, “Eight Letters to a Young Writer,” in which he emerges as a mentor. “Read slowly,” he writes in one of the letters, “like someone studying the network of tunnels underneath a bank vault in preparation for a heist.”

Two years ago, Adebayo and Iduma joined Teju to teach a week-long workshop in Lagos. When he walked into the room, vibrant, one of the participants, the poet and editor Ebenezer Agu, pulled out his phone to find a quote from “Age, Actually,” an essay in Known and Strange Things that looks at Michael Haneke’s film Amour. “I was comparing the voice in the essay with the figure in the room, still trying to step up to the fact that I’d come face to face with the source of the very wisdom I’d looked up to for years,” Agu told me.

Like Agu, who’d come from Nsukka, some other attendees had traveled in from outside Lagos. “If you have any other plans, postpone it,” Teju announced. “We have intense work to do.” He told them what he always told young writers: that the only part of the literary process that was in their control was the sentences in the pages.

Yinka Elujoba also attended the workshop. “He seemed to be measuring every word with his tongue,” Elujoba said. “The way each sentence landed was important to him.”

“For the five days he taught us, I learned more than I’d known about the art and craft of writing,” Agu said. He would have been drawn to Teju’s work because he himself, a poet and prose writer trained in literary criticism, was seeking the intangible, and he knew no one else in the African literary canon he’d been raised on who was reaching for the same.

“I also learnt anew of the man,” Agu said. “He was meticulous, noticed the minute flaws in our writing and most times knew how to correct them. He was emotionally sensitive, too. I learned that it was fine to know and not be modest about it. He is able to reflect upon uncommon modes of expression. The sum of this peculiar model is what I keep sight of in my own practice as a writer.”

Tolu Daniel, another writer and editor who attended the workshop, first met Teju in 2013, at a literary festival in Nigeria, and was surprised that he remembered his name on their second meeting three years later. He, too, began reading Teju from Every Day.

“I definitely agree that his writing has opened up a new tradition in the African literary canon,” Daniel said. “It’s evident in the writing of Emmanuel Iduma, Yinka Elujoba, and a few others.”

One evening, a class ended, and Daniel joined Teju and another participant for a walk. Someone said something about Alice Munro’s short story “The Bear Came Over the Mountain,” which they read in class. Teju thought of one of the characters. One night out in Germany, during the making of Black Paper, a man overdosed and people were trying to revive him. In the phone light shone by someone from above, the scene looked not like a matter of life and death but like theatre, and he brought out his camera and quietly captured it. He thought about that moment of ignition as he walked with the two now. They were in the evening light and ahead of them were faint shadows. Vehicles glided by. It was Ikoyi and the streets looked mundane, blunted of edges. He began to tell them how what is mundane might become charged in the right eyes, with the right vision. “I am always looking for the spark of life,” he said. ♦

If you love what you just read, please consider making a PayPal donation to enable us to publish more like it.

Buy Teju Cole’s books. Open Country Mag may earn an affiliate commission from Amazon.

- Every Day Is for the Thief

- Open City

- Known and Strange Things

- Blind Spot

- Human Archipelago

- Golden Apple of the Sun

- Black Paper

- Fernweh

- Tremor

More Essential, In-depth Stories in African Literature

— DECEMBER 2020: How Tsitsi Dangarembga, with Her Trilogy of Zimbabwe, Overcame

— JANUARY 2021: With Novels & Images, Maaza Mengiste Is Reframing Ethiopian History

— Nigerian Literature Needed Editors. Two Women Stepped in To Groom Them

— Mark Gevisser’s Long Mission of Queer Visibility

— How Lanaire Aderemi Adapted Women’s Resistance into Art

— TJ Benson Holds History and Hope

— Hannah Chukwu’s Call to Help Uplift Unheard Voices

31 Responses

Very engaging, this piece.

Like Teju’s painterly prose, yours reads like flowing water.

I really liked this! Well written piece, Otosirieze. Thank you.

You are a great soul! More power to you, Otosirieze.

This is an incredibly exhaustive profile of Teju Cole.

Otosirieze’s writing matched Teju Cole’s mystical and mysterious intelligence.

Very beautiful piece.

This right here is the kind of writing our age longs for, and it has arrived. I am subdued by the prose—clear water, and its articulate brilliance. A delightful read.