When Daniel Orubo first began reading a lot of Nigerian fiction about LGBTQ life, he found that most of them focused on tragedy. People died. People did not find love. People did not fulfil their dreams. The stories he read mirrored an extremity of life in a homophobic country, where being queer was often a matter of life and death. But there was another extremity that he knew, that he felt was possible, and he was not seeing much of it in the stories.

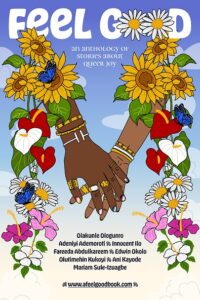

In early 2020, he reached out to Opemipo Aikomo, creative director of the Lagos-based production studio wuruwuru, with an idea: curating a collection of joyous stories. The purpose was to offset the prevalent sadness and trauma in queer narratives. He worked with two co-editors, Olutimehin Kukoyi and Nneoma Kenure, to produce Feel Good. Last December, they published it on a specially designed website. The reception has been positive.

“For the longest time, I used to think stories only had artistic value if they were sad or tragic,” Orubo said. “I believe Feel Good proves that stories of joy and hope can be just as impactful and artistically rich.”

Yet for most of the contributors, writing a happy narrative about the experiences of queer people in Nigeria meant pushing themselves a little further. Their own experiences have been far from joyful. “Plotting, writing, and rewriting the story made me realise that something as seemingly trivial as happiness can be so radical,” said contributor Innocent Ilo.

Even as the entire idea was to create joyful stories, it was important, for the contributors, to recognize the hostility of the country to queer culture. Denying that would have defeated the purpose of the anthology. “What I do know is, the stories I write come from what I know of life, and the biggest thing I know of life is that it is circular,” said co-editor Kukoyi, who received the Gerald Kraak Prize, the continent’s only award for stories about queer life, in 2019.

The reception has been “heartwarming,” Orubo said. “It means so much that people who care about literature were actively championing this project, sharing the stories and asking others to read it. The best feedback I’ve gotten, particularly from queer people, is ‘This actually made me feel good.’ A few of the writers said they had to push themselves to write a joyful queer story, so I hope the positive reception inspires them and other writers to create more stories like this.”

Below, we speak to the editors and contributors of Feel Good.

Daniel Orubo

Can you share the story behind the production and format of Feel Good?

The fact that Feel Good exists is thanks to Opemipo being such a generous collaborator and ally. It was his dream to make an animated short film, and after we worked together on Hanky Panky, he asked me what I wanted to create. He was ready to make it happen with wuruwuru. The initial idea was a limited-edition physical book, but we eventually decided on a website for the sake of accessibility.

How did you go about selecting the eight storytellers? What qualities were you looking for in their work?

I am a big fan of short stories and essays, and I tend to read them whenever they come across my timeline. So I already had a mental list of writers I wanted to work with in some capacity. When the idea for Feel Good came, I started with 20 names. I had read and adored at least two stories from everyone on my list. I knew I wouldn’t be able to get all of them, but I knew I would be happy getting even a quarter of them to agree to the project. As for the qualities I was looking for, I just went with writers who had moved me with their work in the past, regardless of style or theme.

In my experience, the best anthologies have stories that feel singular but with a recognisable thread running through all of them. I wanted that for Feel Good. So besides the “tell a joyful queer story” prompt, I gave the writers free rein to define what joy meant to them and to go in whatever thematic direction felt right. I didn’t want to worry too much about cohesion; I just wanted stories that moved me.

Turning down stories because they didn’t capture the essence of the project, or having writers drop out because of scheduling issues was pretty challenging. I was initially fighting to have at least 10 stories in the project, but I had to eventually accept that the stories we had were more than enough and that the 10 I wanted was just an arbitrary number. I’m stubborn so it took me a while to get there, but I did.

For me, capturing queer joy wasn’t the only goal of this project. Celebrating all of these brilliant writers and their unique styles was just as important.

What was the collaborative process, working with Olutimehin Kukoyi and Nneoma Kenure as co-editors?

Opemipo brought Nneoma on board, and, after one conversation with her, I knew we would work well together. As for Olutimehin — I don’t know if she even remembers this but she edited the first piece of fiction I ever wrote. It was terrible, as first attempts tend to be, but she was so thoughtful and kind with her feedback. I knew she would make the perfect editor for this project.

It was when we had all the stories that we started playing around with placement, to create the best flow and experience. Besides being certain that I wanted to open with Edwin’s story — I just found it so tender and inviting — and have Kunle’s story be the centrepiece because I knew it would resonate with so many people, we just trusted our guts. And when we got that final arrangement, it just felt right to the whole team.

How did you ensure that each story captured the essence of the project?

That was me simply trusting my gut as a lover and obsessive consumer of great stories. Beyond needing to be impressed by prose, plot, and other technicalities, I used my heart as the barometer for whether a story succeeded or not. If I read a submission, and it made me happy-cry, feel warm inside, or feel hopeful, I considered it a success. If it didn’t, we made necessary edit suggestions until it got to that point.

Daniel, I know that this might be a bit of an intractable question, but do you have a favorite story from the anthology?

I love every story for a multitude of reasons — that’s why they all made it — but if I had to pick the stories that resonated with me the most, that would be Kunle’s and Edwin’s. I’m a reluctant romantic, so they are the kind of stories I typically gravitate towards. But what I loved about working on Feel Good was going out of my literary comfort zone and falling in love with different kinds of stories.

Olakunle Ologunro

“The Mathematics of Hooking Up,” with its Internet terminologies, has a specific style and tone. I like to believe that this story, perhaps, might’ve not worked so well if written differently. Was it the style that inspired the story? Or you had to search all the places for the style that fits?

It’s the other way around, I think. The story inspired the style. I was inspired — and even challenged — by the project itself: a book of queer stories that don’t end tragically. For weeks, I kept thinking, making notes, and drafting short paragraphs, all in a bid to get at the heart of what should be the story.

After a few drafts, it became clear to me that I wanted to achieve a tender intimacy, or an intimate tenderness, not just between the characters, but with the reader, too. I wanted to make the reader a witness and a participant in this feeling. Once I realised that, it became easier to blow out the chaff. Easier to let the story speak in its own voice

Daniel, as the editor, how did you perceive the narrative’s contribution to contemporary perceptions of love and hooking up?

From the moment I read the hilarious first paragraph of Kunle’s story, I knew we had a winner on our hands. By the time I got to the final paragraph, I was bawling, and I knew it had to be the centrepiece of the project. I found the story funny, heartwarming, and deeply relatable, and it’s clear that others do, too — it’s currently the most-read Feel Good story. I think that’s because it captures a queer experience that manages to feels both specific and universal. It’s a miracle of a story, and I consider us lucky to have it be a part of Feel Good.

Edwin Okolo

“A Bookish Affair” portrays the intimate moments between the narrator and Mazi, a long-time friend/acquaintance, with a sense of tenderness and restraint at the same time. We know that these characters have both mutually waited for this connection for a very long time. How were you able to strike a balance between building the intimate atmosphere and maintaining the overall tone?

I had spent at least three years mulling over the structure and flow of the story, what to put in and what to leave out, so when the time came to write, it was pretty much a one-take.

The balance in the story is really a sleight of hand. Mazi and the narrator’s love story parallels the love the narrator has for literature, which is embodied in this story by the Ake Book Festival. They can show restraint because they have learned to delay gratification by waiting 11 months for the festival. They can embrace vulnerability because of the safety the festival and the readers who attend embody.

“A Bookish Affair” is a romantic love story couched in a bigger love story, the filial love a person has with their chosen community. It is easy to notice the romantic attraction, but the much subtler filial love is the undercurrent on which the story rides.

Innocent Ilo

“The House of Akwusianubaogu” is exhilarating and intriguing. How was the process of balancing its social commentary — on gender roles, societal expectations, challenges faced by marginalized communities in Nigeria — within the narrative without compromising the feel-good atmosphere? And how does it reflect to you as a person?

Writing “The House of Akwusianubaogu” was a learning experience for me because, for the first time, I had to write a “happy queer story.” Plotting, writing, and rewriting the story made me realise that something as seemingly trivial as happiness can be so radical. I had to be intentional about my characters’ happy ending. And to do this, I had to look beyond the bleak present.

The characters in “The House of Akwusianubaogu” are more brave, more radical, and more intentional about their happiness than I am (obviously). And maybe, someday, I will get to be like them.

OluTimehin Kukoyi

“Feria’s Story” incorporates symbols, such as the orchids, wafers, and the dancing red dress. As someone who’s very interested in symbolism myself, I would like to ask: how were you able to beautifully integrate these into the narrative? How were they chosen, and how did you ensure that they contribute to the subjects the story explores — beauty, self-worth, and of the complexity of human connection?

I’m so thrilled that the symbolism resonated with you because it really is the heart of “Feria’s Story” for me. The narrative moves almost entirely obliquely, inviting readers to experience Feria’s world primarily through her (daydreaming, distant, distracted) eyes. As a character, Feria is very alive to me; in writing her story I feel like I was allowed to borrow the eyes of someone whose whole existence was defined by ineffable things, things which even she wasn’t fully cognizant of her connection to. What Feria sees is really important, and we know she is growing up a bit whenever the story takes us from what she sees to how she sees, especially how she sees her own possibilities in the world.

I didn’t integrate or even choose the symbols in the story, really; they presented themselves. The orchids, the wafers, and especially the dancing red fabric emerged from real memories of mine, all of which were completely unconnected until they hit the page. It wasn’t until we were in the editing phase that I realised, much to my surprised amusement, how little room the story gave me to move away from those moments of Feria experiencing herself and her life through something she could see or something she couldn’t look away from.

I wish I could tell you how I knew the moment with the wafers mattered, or why a stranger’s death was the first thing Feria remembered when she realised that what she was feeling was attraction. What I do know, though, is the stories I write come from what I know of life, and the biggest thing I know of life is that it is circular. Things refer back to themselves all the time; this is how we make meaning of the spectacular randomness that is our existence. It’s just that we’re not all awake to our symbols. We don’t all recognise the cues that reality puts on our paths to remind us that we can choose, we can risk, we can live. I suppose this is something offered by the story’s little (or big) visual, deeply felt moments: a chance to remember that beautiful things die and so do we, so what then? We might as well risk something. We might as well risk love.

Fareeda Abdulkareem

One of my favorite stories in the collection is “Sink & Swim,” because of your coherent use of language, and how you conceptualize social commentary. The story, which I believe is fiction, reads like an essay. Was that a deliberate decision?

Thank you for the compliment. I’m glad you enjoyed the story.

Yes, it was an intentional decision to make “Sink and Swim” read like nonfiction, hence the letter format. This is because I spend more time writing nonfiction and it is where my strength as a writer is clearest. But nonfiction can be constricting. This is where fiction provides a wonderful cover because it permits reckless imagination.

Ani Kayode

I really love Kosara in “Keep This for My Sake” and the setting that you place them in — however hostile. Their struggles seem so real, I couldn’t help but sympathize with them. No matter how strong they appear, you made them so complete that they still break down, which make them all the more believable. Was their character inspired by an actual person you might know? And what advice would you give to marginalized people like Kosara?

While writing Kosara, I wanted to explore the thrilling power of standing up for yourself in a world that does not think you should exist, but I did not want to romanticize it. Because having to defend yourself all the time takes its own toll, especially if you are also subjected to poverty. It can be as damaging as it is liberating if done alone.

I drew on a lot of my own experiences as an openly queer activist in Nigeria, my struggles with housing insecurity, as well as my experience of queer friendships that can sustain, that give you life when it feels like all the world does is take and take from you. I find that almost all characters in anything I write embody aspects of me in some way,

There is a power that comes with not being afraid to dream. As queer people in a country as violently queerphobic as Nigeria, the ability to dream without bounds is a skill necessary for our sustenance and survival. Without it, we fall easy prey to the dehumanising logic so rampant in our societies. But even this dreaming is not easy. The queer liberation struggle is, in the final analysis, still a struggle. There is nothing rosy about it, and, without love, struggle is hard to sustain.

If there is a single thing I hope readers take away from “Keep This for My Sake,” it is that we cannot self-love ourselves out of our need to be loved. It is not a bad thing, it is not a vulnerability or a weakness. On the contrary, isn’t it so wonderfully beautiful that we need each other in that way?

It is important that we think critically about how we conceptualize love. It is so easy to capitulate to the heteronormative definition love currently has in capitalist society, a love that is centered on romantic monogamous pairing, a love that is fashioned in the image and likeness of the nuclear family. In societies like Nigeria where queerness is demonized and criminalized, romantic queer love, precisely because it is prohibited, can feel like the ultimate prize, and it can taste like happiness and freedom. But there is no need to wait to find it before we love without reservation. Just like dreaming, we must also be boundless, unapologetic, and fierce in the way we love, because that is what will sustain us and hold up our resolve until the queer liberation struggle imminently triumphs. ♦

All images supplied by Feel Good team.

If you love what you just read, please consider making a PayPal donation to enable us to publish more like it.

No One Covers African Literature, Nollywood, & Industries Like Open Country Mag

— Country Love Depicts Tenderness in LGBTQ Lives

— The Next Generation of African Literature Is on the Cover of Open Country Mag

— The Fates and Faith of Tunde Onakoya

— How Leila Aboulela Reclaimed the Heroines of Sudan

— Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Is in a Different Place Now

— How Teju Cole Opened a New Path in African Literature

— The Epic, Transformative Comeback of Chidi Mokeme

— Rita Dominic‘s Visions of Character

— The Methods of Damon Galgut

— Maaza Mengiste‘s Chronicles of Ethiopia

— Chude Jideonwo on His SARS Victims Documentary Awaiting Trial

— How Mami Wata Swam to Sundance

— How Dakore Egbuson and Tony Okungbowa Traverse Trauma in YE!

— Writing Omo Ghetto: The Saga, Nollywood’s Highest Grossing Film of All-Time

One Response

Thanks for this.