Spring of 2019: DK Nnuro was in a printing room at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, the machine whirring, spitting up pages of what would become his debut novel. Since the fall of 2016, he had sat at his desk to write it from five to ten a.m. every day, and now, as he watched the complete draft pile up, he was both excited and afraid. He was ready to show the manuscript to the world, but he also worried for the future, what would become of the work once it left his hands and found a life of its own. He collected almost 550 pages from the output tray, and, cradling them like a beloved child, walking down the corridor, he ran into his mentor, the novelist Margot Livesey. “Derek,” she said, “is that your novel you’re holding? Give it to me.”

He handed the manuscript over to Livesey, and so began a rigorous revision process between the young Ghanaian American and the Scottish veteran.

This February, What Napoleon Could Not Do was published by Penguin Random House. It was heralded by Goodreads as one of the “buzziest” debuts, by Essence and Town & Country as a “must-read,” and Open Country Mag had it on its list of the most anticipated books of the year. It was longlisted for the Center for Fiction First Novel Prize, and Vulture and Elle counted it among the best books of 2023. A New York Times reviewer wrote: “Nnuro’s language is economical, precise, but never artless.”

Nnuro, who graduated from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop in 2016, dedicated three years to the manuscript. At the time, he had a postgraduate fellowship and a teaching gig in his pocket, and yet accrued credit card debt. In addition to grit and craft, the realisation of an artistic vision depends on such needs as having food at home. So he allowed himself the kind of material freedom writers needed but could rarely afford. He saw his vision through with a single-mindedness and, in his own way, did something Napoleon could not. The French emperor was, after all, also a failed novelist — his output amounted to 22 pages of an autobiographical romance.

What Napoleon Could Not Do features its own fair share of romance. Its thrust relies on two marriages, between Wilder, an African American Vietnam War veteran, and Belinda, a Ghanaian immigrant to the States, and between Jacob, a Ghanaian man in Ghana, and Patricia, another Ghanaian woman living in the States. These relationships look like love sometimes, seem merely convenient at other times, instinctual needs for “true companionship” stymied by desires for greater validation: Jacob wants a visa, Belinda and Patricia green cards, and Wilder, despite his affluence and heritage, would like a home where his identity doesn’t haunt him to insanity. In a grander sense, it is a novel about the collision of geographical ideas and ideals, regional attitudes and aspirations refracted through characters who “chase America at the risk of tragedy.”

“America is the most well-branded country in the world,” Nnuro says. In the dining area of the Stanley Museum of Art, where he is Curator of Special Projects, he is relaxed in his seat, a wide-brimmed hat riding low on his forehead, behind him a clean curtain wall. Three floors down, Iowa City’s collegiate young go about their lives. He continues, “Jacob and Belinda, like many West Africans, are inebriated by the American ethos and the American spirit and the American dream, things that seem infallible. But when they see these maxims for what they are, branding, something like YouTube advertisements, they are compelled to face the reality of their fragility. The irony of the novel, at least for me, is that I am most emotionally aligned with Wilder, and that’s because I came here at such a young age. I have become a Black American.”

Nnuro was born in Ghana, moved to the United States two days before his eleventh birthday in 1998, and became a citizen within six months. He calls Los Angeles home but returns to Ghana often. His Twi is as fluent as his English, and he’ll have you know that he’s a Mama’s Boy.

Before Iowa, he studied Biomedical Engineering at Johns Hopkins, America’s first research university, in an attempt to repurpose his creative eye for the sciences. Now, two more creative disciplines converge in him: art curation and literary pedagogy. He is an Adjunct Assistant Professor in the University of Iowa’s English Department, and, in this spring, taught a class exploring literary homages and appropriation as a tool for raging against erasure by writers from historically marginalised backgrounds. It was a question he had been engaging for some time.

Once, a short story he submitted for workshop, modelled after William Trevor’s ‘The Piano Tuner’s Wife,’ “made one of the readers forget” about the story he riffed on.

“I remembered then that I had experienced something similar,” he says, his look of probing retrospection disappearing behind a smile, his voice rising in excitement. “Yiyun Li’s ‘Gold Boy, Emerald Girl’ is written in response to William Trevor’s ‘Three people,’ and I thought, Oh, shit! I fuck with Li’s story more than Trevor’s, and that’s when I started looking into homages, specifically how writers of colour are taking the works of white male writers, rewriting them and causing us to forget the originals. It’s a quiet protest but, boy oh boy, it’s fucking powerful!”

While Nnuro’s novel is a slanted homage to Ian McEwan’s Atonement, he situates his work within a tradition of seminal African and African American writers, traces the kernel of his practice to the Ghanaian writer and feminist theorist Ama Ata Aidoo’s Changes, in which a woman leaves an abusive monogamous marriage for the seemingly counterintuitive freedom of polygamy.

“It is increasingly clear to me that if there is a project I’m trying to accomplish,” Nnuro notes, “it is to render how imperialism has complicated the love lives of Ghanaian women, like my mother who has had to make some choices that are not necessarily in lockstep with what we would expect from someone who is, at least ostensibly, as much of a feminist as she is.” His mother lives in Ghana, his father in the United States.

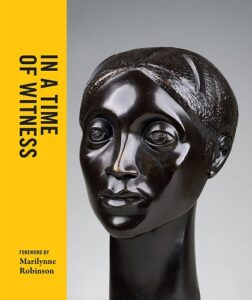

In his curatorial role at the Stanley, Nnuro recently edited In a Time of Witness, a catalogue pairing fine art with ekphrases by 31 writers, poets, and translators who, like him, are alumni of the university. In the book, the past engages the present, the current revisits what came before. Nnuro’s introduction evoking the disequilibrium of the year 2020 — the coronavirus pandemic, Black Lives Matter protests, and Donald Trump — is set against unattributed images of Ere Ibeji, an array of sculptures of twins from Nigeria, and a kente cloth from 20th century Ghana.

Elsewhere in the collection, Sterling HolyWhiteMountain expounds on a ledger drawing of a Native American warrior riding against a colonising US Cavalry in essay form; in Japanese, Minae Mizumura reimagines Yayoi Kusama’s Red No. 28 as a 20-year-old lipstick on a grieving old woman; Tade Ipadeola contributes a Yoruba veneration of Claude Mellan’s 17th century virtuosic engraving of Jesus Christ’s head; and Carmen Maria Machado filters Ana Mendiata’s photographic triptych of death and decay through the eyes of two girls.

“The catalogue responds to our contemporary concerns,” Nnuro says. He believes art has the ethical imperative to speak across time, to recrystallise the failures of history as an education against repetition. He believes he has been called to curation to imbue the interpretive tools of art history with the democratic methods of more narrative forms. In a Time of Witness coalesced organically around ideas of home and freedom, violence and resistance, the sacred and homage, themes the editor himself is preoccupied with in his thought and fiction. They are his answers to questions about the necessity of art.

Nnuro had no formal curatorial education before joining the museum in 2019. He applied after completing his manuscript, and rose through the ranks. His experience with art until then had been from the audience, as an outsider with an aesthetic appreciation and a desire to be moved beyond the limits of capitalist mundanity.

One such encounter took place at the now defunct Corcoran Gallery of Art where, in 2011, he saw 30 Americans, an exhibit featuring 76 works by 31 leading African American artists, including Carrie Mae Weems, Hank Willis Thomas, Nick Cave, and Jean Michel-Basquiat. It was, however, Kehinde Wiley’s Sleep — a large-scale portrait of a supine Black man as Jesus Christ — that stuck with him long enough to go into his novel.

“I was so taken by this vision of Black Jesus,” he says. “It made me think about my own manhood, about vulnerability as it pertains to men, about the dangers of being black in this world. But that’s Kehinde, you know. He’s constantly recasting our understanding of things through a particularly black lens.”

In 2018, Wiley became the first Black artist to paint an official portrait of an American president when he was commissioned by the Smithsonian for Barack Obama. This July, the former president picked What Napoleon Could Not Do for his coveted summer reading list. A triangle of coincidence, perhaps, but an important nod to the debut author’s varied interests and influences.

Obama’s lists are reportedly compiled by him personally. Selection means automatic global visibility for an author and has been known to increase book sales by up to as much as 450%. “It matters to me,” Nnuro says, “that Obama, a man I admire so much, picked up my novel and said, This is a book worth reading.” ♦

“DK Nnuro Finds His Answers” appears in the forthcoming second issue of The Next Generation Series, an Open Country Mag project profiling rising African writers and curators, curated and edited by Otosirieze. The groundbreaking first issue, featuring 16 voices from nine countries, was released in April 2022. The second will be published in 2024.

If you love what you just read, please consider making a PayPal donation to enable us to publish more like it.

More Stories from Open Country Mag‘s The Next Generation Series

— The Overlapping Realisms of Eloghosa Osunde

— How Romeo Oriogun Wrested Poetry from Pain

— Suyi Davies Okungbowa Knows What It Takes

— Why Tobi Eyinade Built Rovingheights, Nigeria’s Biggest Bookstore

— Remy Ngamije on Doek! and the New Age of Namibian Literature

— Ebenezer Agu on 20.35 Africa and Curating New Poetry

— In Writing Cameroonian American Experiences, Nana Nkweti Crosses Genres

— Oghenechovwe Donald Ekpeki‘s Curation of African Speculative Fiction

— Logan February on Their Becoming

— The Cheeky Natives Is Letlhogonolo Mogkoroane and Alma-Nalisha Cele‘s Archive of Intentionality

— Cheswayo Mphanza on Intertextual Poetry and Zambia’s Moment

— The Seminal Breakout of Gbenga Adesina

— Keletso Mopai Owns Her Story and Her Voice

— Troy Onyango on Lolwe and Literary Magazine Publishing in Africa

— At Africa in Dialogue, Gaamangwe Joy Mogami Lures Out Storytelling Truths

— Nnamdi Ehirim Writes from Music

— Khadija Abdalla Bajaber on Fantasy and the Character of Kenyan Writing