Chinelo Okparanta almost did not attend John Freeman’s talk. It was fall of 2011, and she had been working on her fiction at Dey House, the historic Italianate building that houses the Iowa Writer’s Workshop. She was sitting at the back in the reading room, by chance, when the then Granta editor’s event began, and when he said he would collect stories from workshop participants who wished to give him, she printed three and gave him. He boarded a flight back to New York.

“Somewhere over Pennsylvania, my hands started to sweat,” Freeman would say years later about reading her work on that flight. “Here was a real talent. Someone who knew how often the press of love had to find small spaces. Her stories were patient and wise, as if they were written by a woman in her 80s who had condensed all her experience into 12 key narratives.”

Okparanta was only 30 at the time, but Freeman’s appraisal was of the storytelling instincts of a woman who, throughout her life, was privy to Igbo folktales that spanned generations. A woman whose mother, when she was a child, gathered her and her siblings in the dark, during frequent power cuts in Nigeria, and regaled them with traditional stories and songs. She’d subsequently read everything from her mother’s pharmaceutical and chemistry books to her father’s Encyclopedia Britannica, from suspense novels and thrillers to the Babysitter Club series, Camara Laye, and Chinua Achebe. Then she started to write fiction in graduate school at Rutgers University and took creative writing classes. With nudging from her professors, she applied to the Iowa Writers’ Workshop in 2009.

She thought her admission might have been an accident; she doubted herself; everyone but her seemed to know what they were doing. She painstakingly analyzed the work of fellow students she deemed strongest, and did the same for published authors. Publishing was not on her mind then; she just wanted to be a better writer, and she drew from her experiences and curiosities.

One of the stories she wrote there, “Runs Girls,” came about because she wondered what lengths she would be willing to tread to help her mother, who had an illness akin to that of the protagonist’s mother in the story. Visiting her in the hospital, she’d reimagined a reality where her socio-economic condition was difficult enough to force a consideration of sex work. In the story, she explores the implications of such a choice.

Another story, “America,” came from her questions of love and how freedom felt. Her cousin had been working toward an education in the U.S., and this, together with another reimagined reality in which she herself had not moved to America and could not be free, informed the story. The narrator, a woman, eventually gets a visa to be with her female lover.

On our Zoom call in September, Okparanta tells me that these were the stories she gave Freeman. “I handed him the stories and reminded him that he said he would read them,” she remembers. “I think it is a turn of fate that I believed him when he said he would read our stories. You have to take these chances.” Furthermore, the Workshop director Lan Samantha Chang vouched for her.

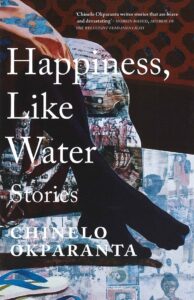

Her career took off. Granta published “Runs Girl” and “America” and named her one of its Six New Voices in 2012. The Caine Prize shortlisted “America” in 2013. That year, Granta Books published her collection of stories, Happiness, Like Water, which won a Lambda Literary Award in 2014, in the category of Lesbian Fiction, and was shortlisted for the Etisalat Prize in 2015. The book stood her out for her ability to weave graceful, affecting stories out of daunting themes—domestic abuse, love, sexuality, religion, and cultural differences—and in refined prose. In the mother-daughter relationships and the parental dynamic of “Runs Girls,” in the beauty standards of the O. Henry Prize-winning “Fairness,” in the lesbian love and idea of freedom of “America,” in the pressures in “On Ohaeto Street” and “Story Story,” she revealed herself to be writing, in essence, about the realities of Nigerian women, of young girls responding to an unsavory world.

While she wrote “America,” Okparanta was aware of Nigeria’s homophobic culture. Even the parents of the narrator express some discomfort that she is lesbian. But she was not ready for the wave of rebuke from some Nigerians. They accused her of being “brainwashed” and “corrupted” by the West. Some made death threats on Facebook. It was personal, virulent, and it hurt. Yet it was only a precursor.

A year later, in a startling turn of events, Nigeria’s then president, Goodluck Jonathan, signed the anti-gay bill into law. The Same-Sex Marriage Prohibition Act took effect in January 2014, criminalizing same-sex relationships, with a 14-year jail term for people who are “homosexual” and 10 years for anyone found to be “promoting the act.” The law was not the worst sentence. In some parts of the country, punishment by stoning was acceptable, as was assault on gay men and women. The bill was first drafted in 2006 and put before the National Assembly in 2007, but when her book was coming out, Okparanta had not been quite sure where it stood. “At that point, it could have been a completely forgotten bill,” she remembers. Its adoption was sudden and followed by commendation from most Nigerians.

Activists and a few public figures spoke against it, including, notably, the novelist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, as well as Bernardine Evaristo and Helon Habila. The late Kenyan writer Binyavanga Wainaina, spurred by arguments surrounding gay rights in African countries, announced that he was gay.

“Goodluck Jonathan simply brought the issue to the forefront by following through with the signing of it,” Okparanta told the novelist Nicole Dennis-Benn in an interview for Mosaic Magazine in July of 2014. “Yes, Nigerians are very homophobic, but I think many are so simply out of fear of the unfamiliar. In my stories I attempt to open the discussion on the topic, so as to give a voice to all the Nigerians out there who have been forced to live in hiding. I did worry, after I had written the stories, about how they would be received in Nigeria. I’m not by nature a scandalous person, but I do believe that certain stories need to be told. Now when I look back on it, I’m glad that I wrote those stories, and I’m glad that I sent them off into the world, because, beyond being beautiful love stories, I do believe that they are also necessary stories of love.”

The implication of the anti-gay law was varied. Okparanta feared for her safety, and thought of canceling her travel to Nigeria for the Etisalat Prize ceremony. It also created a dilemma for her next book, whose two central characters are lesbian.

Okparanta had always thought about her mother’s stories of the Biafran War. They were tragic tales, of how her mother lost her father in the carnage, of young soldiers who never returned home, of starving children, bombing raids, heaps of corpses. The stories stayed with her, and, alongside them, her thoughts of love and freedom persisted. She saved it all for her first novel.

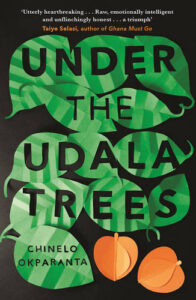

She was already writing Under the Udala Trees when she underwent the heat for “America.” Then the anti-gay law, which only served to spur her. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt published it in 2015, to acclaim, and, predictably, more backlash in Nigeria.

Under the Udala Trees is a coming-of-age story about Ijeoma, a young Igbo Christian girl whose father is killed in an air raid as the war breaks out in 1967. She is sent to another town for safety, and there she meets Amina, a Northern Muslim girl, and their friendship grows into love. When their relationship is discovered, Ijeoma becomes aware of a society averse to her sexuality. She buckles under the weight of her conflicting beliefs, her mother’s resistance, what is expected of her as a young woman, and her repressed desire to live and love openly. Eventually, she comes to terms with herself.

Okparanta taking on the Biafran War, LGBTQ+ love, Christian-Muslim romance in the ‘70s, and inter-ethnic tensions between the Igbo and the Hausa was a quadruple landmine of sorts—these are still some of the most contentious subjects in Nigeria. But she felt no pressure. “Was I aware of the potential arguments and conversations that might ensue? Yes. But I will still write the story and try to make the story work. The worry comes later, after I have finished writing.”

After the book’s release, she told The Rumpus that it “seeks to open up—make transparent—the lives of these particular members of Nigeria’s LGBTQ community, so that those with a hatred for same-sex love might see just how human same-sex love really is. Nothing to be afraid of. Certainly nothing deserving of punishment.” She added, “This ability to expose—to make transparent—is the power of literature.”

But the clouds of homophobia hovered close. It greeted her at the Ake Book and Arts Festival, in 2016, where she was a panelist, and was forced to respond to provocative questioning. The event spilled into social media and arguments ensued in some literary quarters. Later, a radio host told her not to mention the “LGBT elements” of the book on air, fearing the station would be fined.

Still, there were more than a few readers who expressed gratitude for what Okparanta had done. It had not been done on this scale before, African lesbians at the center of a novel, and from a writer with marked skill, heralding a shift in the direction of Nigerian literature. For emerging LGBTQ+ writers and even her peers, Okparanta had become something of a waymaker.

“Chinelo Okparanta is a formidable force,” the Zimbabwean novelist NoViolet Bulawayo, a friend of hers, told me. “She doesn’t tell easy stories, she tells necessary, even earth-shifting ones—the initial reception of Under the Udala Trees is a good case of the impact of her work. We know a writer is actually doing their job right when they make people lose their shit. They are also doing an even more important job when they make others possible. In choosing to tell humanizing stories that defied the literary trends and silence around African queer life, Chinelo became an important part of the reason why we are today in a position to celebrate the flourishing of writing that rightly holds African queerness to the sun.”

Under the Udala Trees earned a positive reception on the international front. It was a New York Times Book Review Editors’ Choice and one of NPR’s Best Books of 2015. It won her a second Lambda Literary Award for Lesbian Fiction, was an International Dublin Literary Award finalist, and was nominated for the NAACP Image Award for Outstanding Literary Work of Fiction and longlisted for the Center for Fiction First Novel Prize. It also landed her on Granta’s 2017 list of the Best of Young American Novelists.

Yet, contrary to much of the reception for the book, Okparanta had not merely written an “LGBTQ story.” Inherent in her work is a tender force, a quality of humanness. “I think, as I write, there is something in me that still writes to that larger human community which we all have to exist in in the end,” she says.

The Nigerian novelist Helon Habila feels that Okparanta challenges categorisation. “I think she has been a champion for marginalized and underprivileged voices throughout her career,” he told me, but “Chinelo Okparanta is more than just an LGBTQ writer. She pushes the envelope in terms of what it means to be an African writer.”

Seven years later, a lot has changed across the continent. In some African countries, the culture has either loosened or tightened some of its homophobia. In Nigeria, a new generation of voices has risen, unafraid to tell diverse stories through their queerness, in spite of the risks. Assaults continued against queer people, backed by law, and yet society was catching up slowly, with queerness visible.

Okparanta has never been one to satisfy society, anyway. “The morality of any society is always changing,” she says. “What we agreed on in 1990 looks different from what we agree is acceptable in 2022. Look at race relations and LGBTQ+ identities and how much society has shifted on both fronts. You can’t go by what society is saying just because it’s popular, which is something I’ve always been wary of. You have to try to interrogate things from your own moral compass, which can only be based on your own humanity.”

Okparanta has always been interested in what society considers “controversial subjects.” In 2016, she taught a class at Columbia University, titled “The Ethics of Writing Other Cultures.” Her class read Kathryn Stockett’s The Help, Arthur Golden’s Memoirs of a Geisha, and Adam Johnson’s The Orphan Master’s Son, all white writers who wrote about non-white cultures. The discussion leaned into whether writers could do this, and she remembers mentioning James Baldwin’s famous defense of Styron, a privileged white man who wrote about Black slave rebellion in The Confessions of Nat Turner. Baldwin’s argument: no one should tell a writer what they could or could not write. Many of Okparanta’s students agreed. Next came the question of how to go about it.

She wanted to probe the subject of cultural appropriation, draw her own perspectives and hear from her students. The conversation became heated and nobody seemed to agree on anything, except that some books failed and others succeeded, and that some books that had been accepted in the past would be unacceptable today.

The next summer, Okparanta moved to a more conservative part of Pennsylvania in the U.S. Donald Trump was now president and the country was racially charged. She observed the hostility between the American left and the right. That, coupled with her class at Columbia, gave her the idea for a new fiction character named Harry Sylvester Bird, a white middle-class man who begins to identify as Black. She had previously tried to write about race and it did not turn out well, and she doubted she would again. But she did not fight the idea this time. Instead, she started work on a novel, seen from his perspective.

“When Harry came to me, he came for a reason,” she tells me. “When he decided he was ‘Black,’ he decided it for a reason. When he decided to come as a very satirical character that also feels real, I was like, let’s go with it. I write from a place of honoring the story I have been inspired to tell. I write from a place of honoring the characters that come to my imagination. If I do anything else, I think it will make it harder to write, and not as honest of a work. You would feel it is not from a true place.”

She knows that she is not immune to the literary pigeonholing that many Black African writers face, that the women are expected to write only about female sexuality, motherhood and marriage, and corruption in their home countries. “They pigeonhole you to the point where they don’t understand how else to read you,” she says. “You have to be the one to sort of guide them, to say, yes, this is true, but all these other things are also true. I am a creative inspired by the world around me, but I will still create worlds that are unlike my own, and create characters not quite like me.”

She told me that she intended to play around with the idea of entering other cultures, simultaneously interrogating “but without giving a clear answer.” “One has to be aware of the power dynamics that are going on, and to make sure that there is some kind of nod to the fact that you know what you are doing.”

Because her first two books follow young Black African women, because the books were groundbreaking for lesbian representation in African literature, people assume that a satire about a white cisgender heterosexual conservative man is the sharpest deviation for Okparanta. Not many are aware of her background in contemporary and historical satirical literature, her master’s in 17th and 18th Century English Literature, a period rife with such works. She liked Voltaire’s Candide, as a teenager, and, later, Jonathan Swift’s A Modest Proposal and Paul Beatty’s The Sellout, struck by their acute and unflinching critique of society.

She was aware of the risk of writing satire; many stories that deal harsh criticism on society meet negative reception or do not even get published. She also knew that the genre could be slippery for readers. She told PEN, “It’s always easy to look at the work superficially, and satire can often come off as superficial, but a devoted reader will hopefully keep in mind that, in satire, context matters. History matters. The contemporary politics of the day matter—and in a manner that is more than meets the eye.”

She tells me that the idea of the “hot topic” has never appealed to her. “I am thinking about incidents that inspire my creativity in a different kind of way.” But she understands the risk with her approach. “I think, sometimes, it takes time for people to digest what literature is really doing.”

Harry Sylvester Bird is, in fact, most about Black and African experiences of racism in America, subverting how white people and Westerners write about Africa. She only went the unconventional route of writing it from the perspective of a white man.

Harry is, by design, an exaggerated character, full of the distasteful traits of well-meaning liberalism. The first part of the book follows his unremarkable middle-class life in Edward, with neglectful parents who hate each other, and who are also obscenely racist. In his own assured anti-racist mentality, Harry loathes them. He escapes to New York, in the second part of the book, and resolves to shed his whiteness. There, he meets and falls in love with Maryam, a Nigerian woman, and their relationship forces him to truly come to terms with his identity. He is seemingly sympathetic, but his is ultimately a performed allyship, and he is oblivious to the racist connotations of his actions.

“It’s the kind of liberalism that aims to support, but in supporting with such alacrity, tends to overdo,” Okparanta says. “The tragedy actually belongs to the Black African community. It is not only in Maryam, but it is also in the people Harry meets in Tanzania, the way he sees the children in Ghana.”

Okparanta tells me that she had never seen a book like hers, with its unusual approach. It appears to her to be why many people, particularly white Americans, are uncomfortable with it.

“They don’t know what to make of it,” she says. “They can’t quite condemn it. They can’t quite find the angle through which they can make a complete condemnation of it, so they get stuck. What do you do with a world that is not black and white? For me, that is when empathy comes into play, where you have to go beyond the black and white and look at the nuances. And when you can’t find any other meaning, it’s good to go to that humanistic core and ask what is going on. Where can I empathize with the character? How does it apply to me and how can I improve myself from that story?”

After the book came out in July, Okparanta told The Republic that seeing its humor depended on a number of factors, listing “the reader’s racial and socioeconomic status, outlook on race and race-related historical atrocities, level of identification with certain childhood traumas, and perhaps most importantly, the reader’s sense of humor.” This may be why I, a Nigerian in Nigeria, an outsider to the experiences in the book, can afford to regard it from the safe distance of an amused observer, and find its charm and wit.

The question of geography and expectation first arose in conversations on Okparanta’s work when “America” came out in Nigeria, with her portrayal of the character’s expectation that it would be a country of freedom. It didn’t sit well with the homophobes. Now Okparanta notes that some white Americans take offense to her new portrayal of the U.S. purely for political reasons. “I think it is interesting that they are willing to take the positive but not the negative,” she says.

America entered Okparanta’s world at the age of 10, when she and her family left Nigeria so her father could pursue a graduate degree at Boston University. It was the 1990s, and, for a wide-eyed girl from Nigeria, the notion of the American dream was potent. “As a child, I was told that everything in America is better, shinier,” she remembers.

It seemed true initially, with the smooth roads and the gleaming grocery stores. Then, after the family began to experience mistreatment, a slow realization: this place they so elevated was not all perfect. Her classmates didn’t understand her even though she spoke English. They bullied her on the school bus, both white and Black American children, called her racist names and asked whether she had lived on a tree.

Her family home offered no respite. She suffered abuse, and remembers her and her siblings always being afraid, speaking in hushed tones, shrinking into themselves. She was raised a Jehovah’s Witness and read their publications, wanting to know their stance on domestic violence.

She began writing a year later, aged 11, after she won a city-wide essay competition in Boston. Her essay was on domestic abuse and it was the first time she figured that whatever she had to say was important.

The U.S. is where she was formed with strong views of the world, and she might as well be entitled to say everything she wanted about the country. Being a Nigerian woman in America has granted her an understanding of both cultures, as an insider as well as an outsider. “The narrative initially is that everything is positive,” she says, “and then it takes you time to realize how the system can help you but also can harm you in many ways.”

The blind spots of American culture have questioned her last two books now. When Under the Udala Trees came out, she was shocked that a few people said to her, “Well, we’ve moved on from that. Same-sex marriage is now legal in the United States, so what’s the point writing that book?” She brought it up in an interview with The Rumpus. “I look at the people making the statement and I can just smell the privilege wafting out of them like perfume,” she said. “And, I think to myself: this is the problem with privilege. When we live in our own privileged little bubble, it is convenient to pretend that all is well with the world, that everyone enjoys the same privileges that we do. We conveniently forget that there are others, sometimes our very own next-door neighbors, who suffer in ways that we do not. I think the novel is a testament to this: a reminder that just because we perceive ourselves free does not mean that everyone is indeed free. Even in America there are communities in which gays and lesbians and bisexuals and transgenders are still persecuted. Less than two weeks ago a transgender woman was shot dead in a shopping center in Maryland. These things still happen, yes, even in America, and to turn a blind eye to them is to do a disservice to our own humanity. If we say to ourselves that there is no more homophobia in the United States, that the LGBTQ community no longer faces discrimination here, we are simply deceiving ourselves.”

NoViolet Bulawayo understands Okparanta’s angle. “With Harry Sylvester Bird, she continues to provoke, but in a radically creative way that carves out new territory and shows her range,” Bulawayo told me. “I can’t think of a fitting way to write about American racism in this moment than through satire. And this is satire that is deeply unsettling, scathing, but I wouldn’t expect any less of a novel in which the racist, often mortifying white protagonist believes he is, yes, black, an ally, and far removed from his racist parents from whom he desperately wants to distance himself. Hence the comedy. But given how true this book feels, how firmly rooted in our time and the near future we all know has its arms firmly linked with America’s racist past and present, the comedy becomes the ominous kind. Harry Sylvester Bird is here to haunt us, and to demand our attention, just like its writer’s imagination.”

Bulawayo went on to cite the Zimbabwean writer Yvonne Vera. “When [she] wrote: ‘A woman writer must have an imagination that is plain stubborn, that can invent new gods and banish ineffectual ones,’ it is easy to think that Chinelo is the kind of writer she had in mind. What an incisive, rigorous intellect, what a potent, powerful voice, what a plain stubborn imagination.”

Okparanta once described herself as “an activist and an artist.” But as the novelist Sarah Ladipo Manyika observes, “For some writers, the thematics, or politics, of their work trumps craft, but not so for Okparanta.” Perhaps it is because, beyond sexuality, culture, or race, it is human beings that she prioritizes. Behind the author’s own composure is an assertive personality—a strength recognizable in her fiction.

“I believe the most consistently distinguishing factor in Okparanta’s work is its intelligent approach to identities—in their diverse forms,” the Nigerian novelist Chigozie Obioma told me. “Her fiction reveals a mind that is at once compassionate as it is ambitious. But it is the intensity of her approach that sets her apart, and the reason, I think, her work will endure and be read for years to come.”

It is that empathy that is most intrinsic in Okparanta’s work. In “America,” she approaches the opposition of Nnenna’s parents to her sexual orientation not from their hate but from a place of reasonable fear. In Harry Sylvester Bird, she questions the complicity of white liberals in racial prejudice, but is still defensive of Harry the person, who has endured a difficult childhood with a bigot father and a distant mother. Beyond that conversation of political correctness, she says, “it makes sense to be understanding of his journey.”

But Okparanta’s empathy does not end on the page. She is committed to helping people in her communities however she can. “It flies under the radar how much of a presence Chinelo has been for younger queer writers, which is partly because of how understated she is in public,” said Open Country Mag editor Otosirieze. “We don’t think of her as an icon just because of the success of her work; for me, it’s about her mission, which I think is to lift others. Several African writers of her generation are successful, but only a handful acknowledge that there are people behind them, that those people might have different barriers. Not only is she one of them, she means it.”

There were times when Okparanta felt alone, though. Becoming the highest profile African fiction author who made her name exploring queerness ensured that. It may have been even more difficult knowing that many writers cite and look to her resilience, to figure out how they themselves might confront society’s limitations to living freely, to understanding the world, and in telling meaningful stories.

She remembers receiving support from unlikely places. She met a priest who turned out to be an ally, “like, a real one, not in the Harry way,” she laughs. She understands that not everyone knows what to do. “I think, sometimes, we think we are alone, but we are not always as alone as we feel. Community really matters. Community support exists. But we have to also be willing to support one another.” ♦

Edited by Otosirieze.

If you love what you just read, please consider making a PayPal donation to enable us to publish more like it.

Buy Chinelo Okparanta’s books. Open Country Mag may earn an affiliate commission from Amazon.

More Essential, In-depth Stories in African Literature and Nigerian Film & TV

— Cover Story, April 2022: The Next Generation of African Literature

— Cover Story, February 2022: The Methods of Damon Galgut

— Cover Story, September 2021: Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Is in a Different Place Now

— Cover Story, July 2021: How Teju Cole Opened a New Path in African Literature

— Cover Story, January 2021: With Novels & Images, Maaza Mengiste Is Reframing Ethiopian History

— Cover Story, December 2020: How Tsitsi Dangarembga, with Her Trilogy of Zimbabwe, Overcame

— Awaiting Trial: Families of SARS Victims Speak in Devastating Documentary

— The Making of Mami Wata, Nigeria’s First Film to Premiere at Sundance

— How Dakore Egbuson and Tony Okungbowa Traverse Trauma in YE!

— Mark Gevisser’s Long Mission of Queer Visibility

— How Lanaire Aderemi Adapted Women’s Resistance into Art

— Writing Omo Ghetto: The Saga, Nollywood’s Highest Grossing Film of All-Time

— Country Love Depicts Tenderness in LGBTQ Lives