Nsukka. 2013. The university town hummed with quiet energy, cradling thousands of outsize dreams. Nineteen-year-old Arinze Ifeakandu pulsed with a story that came complete: characters, plot, language. All that he’d written led up to this one. He started writing in a frenzy, on a laptop with a faulty battery. His friends called the laptop Television, for the way it turned on only while plugged to power and off when the unpredictable electricity winked out. But he’d learned to perfect his Control S game; the story was much too precious. He took Television everywhere, from the English department to the Christ Church Chapel choir room. He most preferred the classroom, after everyone left for the day, away from the chaos of the boys’ hostels.

He woke in the middle of the night to work. Something indecipherable drove him. The story rushed forth, unbidden. In it, two male undergrads struggle to hold on to one another as their romance buckles beneath family and social constraints. It was personal, an expression of his yearning. He called it “God’s Children Are Little Broken Things.”

The story was, in many ways, definitive, of his tender hand and the writer he would still become. One with a keen understanding of human sensibility, who could trace the jagged edges of pain, whose stories would be an unflinching perusal of desire and sensuality, with concrete characters that had lived for years within his thoughts, many unmoored by heartbreak, and others held together by the grip of love. It was a teenager finding his voice.

Much of “God’s Children” takes place in Nsukka, in the southeast of the country, but for the rest of its inspiration, he sifted his memories of Sabon Gari, in the northern city of Kano, where he grew up.

Life in Sabon Gari was simple but dramatic. A small suburb bursting at the seams, crammed with bungalows, the streets brimming with people, it held, in a self-sufficient way, almost everything that its inhabitants needed. It was often loud, thrumming with local energy. “Sabon Gari” is Hausa for Strangers’ Quarters or New Town, because its ethnically mixed inhabitants were mostly non-Hausa and non-Muslim, and often Igbo and Christian, which meant that, on weekends, people from other districts streamed in to party, to avoid the restrictions of Sharia Law in other Kano districts.

There was never a dull moment. Drugs were rampant, and the occasional NDLEA raids sent crooks and criminals scrambling. When fights ensued, people leapt out of their compounds to watch the spectacle. When power went out, they gathered in front of their homes to trade gossip. Deserted streets meant that power was back on, and everyone was indoors watching TV before it inevitably went out again. At nights, the homeless took over the streets.

The constant drama did not eclipse the sense of community. Families interacted with one another. At home, his own spoke Igbo. Outside, pidgin was a unifier. And as the sun waned, he roughed around playing football with other children.

He had a joyous childhood, despite what he calls “wide spates of stress.” There was love at home. There was music, too. He remembers guitar strums and the sweet lilt of the keyboard at morning devotion; most of his family belonged to the church choir or band. It was large and close knit, aunts and uncles and distant grand cousins, all huddled in the same town. His grandmother was something of a glue.

Before the bleak years that followed, there were bouts of financial prosperity during Obasanjo’s presidency in the early 2000s. His mother was a primary school teacher, and still is. His father travelled often on account of his job. Goodbyes were tough; Arinze was a daddy’s boy.

Unlike his brothers, he was not very sociable. He liked to play but loved more to read. There weren’t many books around so he collected old discarded ones. The older he grew, the more he got the books he wanted, the less he went outside. He read everything, including inappropriate adult content. He spent any pocket money he could scrounge together on books; the shoddily published ones, he remembered, with laughable tropes.

The first time he had access to a library was in secondary school, and he started reading seriously: plays by D. Olu Olagoke, books on Islamic history. He was writing, too. He shared his stories with his mother and his Uncle Chidi. Sometimes, he spun tales for his siblings and cousins. He was always proud showing his uncles a new poem; they read, full of encouragement.

Later, when his stories turned “gayer,” he stopped giving them to his mother and uncle to read, wary of their response. By then, relatives would read his work but evade questions of his sexuality.

In senior class, his taste began to sieve itself. He found that Dan Brown and JK Rowling, despite their popularity, did not resonate with him. He was moved instead by Chinua Achebe and Buchi Emecheta. He read Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Purple Hibiscus, set in the university town of Nsukka. “For me, when I read Purple Hibiscus, it made me think of a certain kind of intellectual Nigeria. The book itself sort of conjures that feeling of place that is so deeply rooted, you feel that sense of nostalgia. It made me think of Nsukka, the institution, as great.”

With this rose-tinted impression, he enrolled at the University of Nigeria, to study English. He felt validated when he walked the storied halls and saw Achebe’s old office, listened as the lecturers recounted personal encounters with the great writer. Nsukka had a story and he wanted to be a part of it.

Ifeakandu went to Nsukka with an understanding of an artistic community, of exchanging stories with reader-writer friends. On his first night in Alvan Hall, he learned of a group of creative writers on campus. He read their work the next day, poems and stories pinned to the department’s notice board. They called themselves The Writer’s Community (TWC).

“Imagine being a teenager and being so full of that dream,” he said to me. “And then you’re not the only one. You have all these other people who feel similarly and there is a spark because outside of the love for arts, outside of the love for writing and literature which we all share, there is a certain kind of socio-political awareness. There’s also a certain kind of collective dream, which was we: want to be great writers, we want to publish books and be read.”

He had read Adichie’s Half of a Yellow Sun and Achebe’s There Was a Country and knew of the friendship between Achebe and the late poet Christopher Okigbo, and was charmed by the “intellectual romance”: “So basically, it’s in that air, and you’re, like, yes, we, too. I guess, for me, that’s what Nsukka did. I was just swept up in that dream, you know, which is, like, we have a sort of intellectual rigor, a sort of sociopolitical involvement through our own artistic practice. And I think it’s a very powerful experience to have because there’s a way in which art can be sterilized.”

At TWC meetings, they had conversations on craft, ambitious friends honing their art without teachers, and their talks were buoyed by this sense of purpose, what he describes as a “faith in artistic practice as more than us, larger than us.” He put it this way: “It’s, like, I want to write something very good. I want to write something very beautiful, but I also want to write something meaningful because, you know, we have a goal, and that goal is to make our society more loving. And, again, sometimes it’s, like, is this a childish dream? What power do we have? But we believed it, and we believed in each other, and we did it, and we continue to do it.”

His time in the English department was not all ideal. The curriculum rendered reading herculean, and he nearly lost his joy for it, what with the sheer number of titles they were expected to complete in a semester. He preferred Junot Diaz and Jhumpa Lahiri to “the neoclassical shit.” “I’m, like, bro, who told you I came here to be reading about Americans in the frontier?” he joked.

Some English majors looked down on Engineering students — and Ifeakandu himself loathed engaging in arguments with engineers — or fancied themselves “the next Heidegger” while they dressed illogical arguments in big words. He became prose editor at The Muse, the department’s critical and creative writing journal and, since 1963, the oldest in West Africa. He would eventually serve as its editor and bag an interview with Adichie. But even then, the journal was highly politicized, which prevented it from publishing the best work.

He couldn’t wait for Saturdays, when he could escape to TWC, which was smaller, more intimate, realer, untethered to the politics of the English department even as it drew members from there. At the time, the group held, among others, Open Country Mag editor Otosirieze, 20.35 Africa founder Ebenezer Agu, the visual artist Osinachi, the children’s author Adaeze Nwadike, the poet Chisom Okafor, and the photographer Michael Umoh. They met in the Faculty of Arts quadrangle or at a quad beside the university’s abandoned children’s library. Meetings were marked by laughter, impassioned arguments, a celebration of queerness, stories. In that space of open air and wilting concrete, the future came alive. (Disclosure: I was custodian of TWC, years after the writers listed.)

“An ideal day involved a beautiful story or poem, you know, that piece we all know someone has been working at, trying to get it just right,” Ifeakandu said of their time. “I loved our arguments, and our radical optimism. I loved the way we inspired each other — I felt mighty inspired, at least. Beautiful work inspired me, and beautiful character inspired me, and it was abundant — not perfection but a commitment to work that matters, even if only to the writer. We loved literature and we believed that it mattered, truly mattered. Time can chip away at some of that faith — it is always worth rekindling.”

It was at this point of refreshment that “God’s Children Are Little Broken Things” came to him. Every Saturday, he brought his laptop, Television, to TWC, and after the meeting he resumed work on the story.

That year, 2013, he attended the Farafina Writing Workshop, taught by Adichie and Binyavanga Wainaina. He embarked on a short story collection, in a bid to become a better writer for a novel. “It’s one of those ideas that people have,” he says. “Maybe it did make me a better writer.”

His first round of recognition began two years afterwards, when A Public Space awarded him a Writing Fellowship and published “God’s Children.” Then the Babishai-Niwe Poetry Award put him on its shortlist. And then, in 2017, the Caine Prize shortlisted “God’s Children,” and, at 22, he became the second youngest finalist in the prize’s history.

“I’d never traveled out of the country, so I was like, ah, God, if they shortlist me, I will just travel.” He was elated. “And they did. I traveled out of the country for the first time, and that was quite an experience.”

Attending the awards ceremony in London gave him a sense of expansiveness. “It’s, like, you’ve traveled, you’ve been treated well as a writer. You’ve been made to feel special for a period of time. So, you’re, like, this is the public aspect of my career, and this is what I want my career to look like more often. You’re, like, okay, I’m going to have to go back and do more work, you know?”

The collection came together in the years that followed, as Ifeakandu began his MFA at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. His prose was better now, measured, and he drew tales of surreptitious affairs, incandescent loves and desires, and men who tread warily under cultural pressure and socio-political strife.

He wrote “The Dreamer’s Litany,” about a married Hausa shop-owner who starts an affair with a wealthy, older Igbo man, and “Good Intentions,” in which a lecturer’s affair with his male student is discovered. He added “Where the Heart Sleeps,” about a young woman growing closer to her deceased father’s partner, and “A Mother’s Love,” in which a man deals with grief. In “Happy Is a Doing Word,” society intrudes on the fledgling affection between two boys in a way that reverberates through their lives. In “What the Singers Say About Love,” a rising young musician and his lover are wrested apart by the demands of celebrity.

He was also concerned with the character of places. He wrote about both “decay-and-slang Sabon Gari” and sun-baked, larger-than-life Sabon Gari, about Nsukka of nostalgia and dreams. He dotted his stories with features of the towns, painted them to life. Something in him retreats when a place feels stripped down. He interspersed the dialogue with unitalicized Igbo and Pidgin and Hausa, consciously infusing what he calls “local color.” He believed that storytelling should expose, that anything less removed from the realness of his work. Reality, played out “in a million dramatized permutations.” Heartbreak pervaded the stories. That devotion to realism, to the unembellished tangibility of his characters, meant that the characters rarely experience triumph. He felt that the best books had a sense of truth to them, and he was a realist through and through.

By the time “The Dreamer’s Litany” appeared in One Story, he was rewriting an older story called “Michael’s Possessions.” He wrote “Alobam,” which came out in Guernica. Some stories changed over redrafts. When he met his agent, Jin Auh of The Wylie Agency, she asked him, “How is it that you have stories in A Public Space and One Story and you still don’t have an agent?” It was the harsh reality of Western publishing’s investment in African literature, where class, not talent, was the first determinant of success.

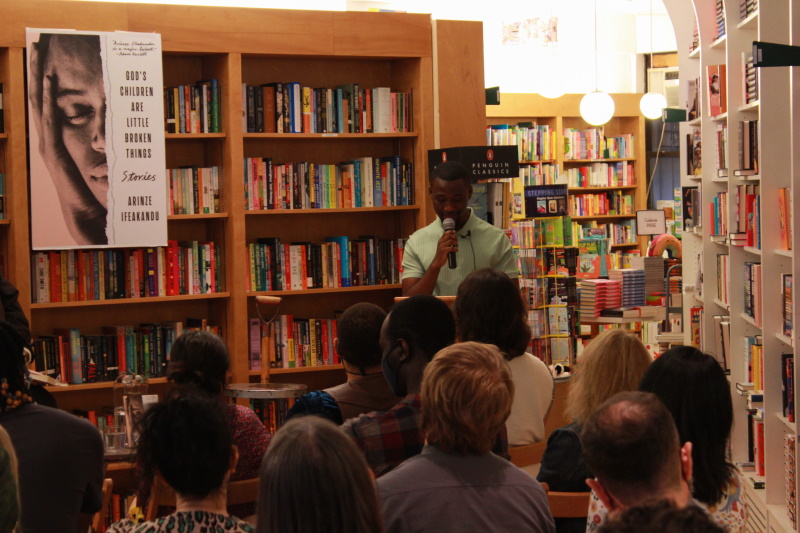

When they sent God’s Children Are Little Broken Things out, Ifeakandu weathered a suggestion by publishers to change the book’s title. A Public Space Books acquired US rights and Weidenfeld & Nicolson (W&N) won UK and Commonwealth (except Canada) rights in a four-way auction. The book arrived in June of 2022, just after he received a nomination for The Future Awards Africa Prize for Art and Literature. There was a launch in New York City, with the novelist Brandon Taylor.

“For many years, the characters kept me company, kind companions for the moments,” he said then. “They were there in Nsukka, where I began the collection in 2013; there at my first heartbreak; there when I tried America and ached for home. When overwhelmed with questions — Why is the world this way? What is Nigeria doing to us, the young, and what has it done to our parents? Who is the man emerging from the pyres of this inner boy? — I found a listener in my ever-silent computer and, at the end of every road, the beauty and truth of life ordered in language.”

The blurbs came. Damon Galgut praised the book as a “beautiful, significant debut” of “quietly transgressive stories,” and Edmund White hailed him as “a writer of lyricism and profundity at the beginning of a brilliant career.” Colm Tóibín wrote, “They dramatize what love is like, in a time when love is under siege.” Eloghosa Osunde called it “Magic in motion.” There were lofty comparisons, too, to Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and Zadie Smith. The book drew breakout acclaim.

Open Country Mag named it a Notable Book of the Year. In a review, the critic Emmanuel Esomnofu noted about the characters: “So real are they, you could almost reach out and touch them; so easily could you make their complications yours, untangling their excesses and poring over the minute details.”

Later, it won the Dylan Thomas Prize and the inaugural Republic of Consciousness Prize for the US and Canada, was a finalist for the Kirkus Prize, and earned a spotlight honour from the Story Prize.

“It is one thing to write a good book, it is another for it to get into the hands and minds of the masses,” he told us then. “I didn’t know how the journey would go, I just had this faith that people would appreciate it. Increasingly, I feel like I have a future in this field, that I will not be broke, and it buys me enough stillness to continue working.”

“Tender” is a word often ascribed to Ifeakandu’s work. His stories take on a distinct sensitivity, all the more striking for their precision. The candid yet gentle treatment that defines his prose was careful, from a harrowing scene of sexual assault at the end of one story, to suicide and levels of trauma. The men in his stories sometimes flail and the women they inevitably hurt bristle with resentment. Their joys, as much as their pain, are stark against the backdrop of a repressive, homophobic society.

That tenderness was evident on our Zoom call. He had a gentle disposition that belied his high-spiritedness. He was animated when he spoke and was full of quips. When he laughed, it was loud and full and unbridled.

“I have chosen not to be a slave to the dictates of this ignorant, hateful society,” he said. “I have one life and I’m going to live it authentically. I’m going to pursue my own joy. I’m going to pursue what fulfils me.”

What he learned in the last few years was that he had a voice, that he could make it loud.

When he was a child, playing games with peers, Ifeakandu preferred the effeminate roles. He dressed as the woman or acted the mother. “The kids around me understood that,” he said. “They just understood, ‘Oh, yeah, Arinze dey do like girl, Arinze likes to play mummy.’ It was just a fact of life. There was nothing to it.” He had crushes on male friends and the boys in Westlife. To him, girls were beautiful in factual ways; but boys — he wanted to hold them. He went on white American erotica websites seeking stories of gay love. “I assumed everyone felt what I felt for boys.”

At first, those feelings were sequestered from shame. But boarding school, as it tends to do, eroded that innocence. The Nigerian Anglican church had begun to express misgivings as sexuality became more central to conversations in Western countries. At his Anglican school in Awka, the priests told the boys not to hold hands.

“It was just like sexualizing the intimacy that boys share,” he recalled. “And then witch-hunting teenagers who were discovering themselves. It was almost as if these priests felt empowered by their bishops and archbishops who had travelled for conferences, to reinforce a certain kind of violent homophobia in response to what was happening in the West.”

At the same time, he was bullied, pelted by words: sissy, homo. Classmates and seniors asked him: Kee ife i na-eme ka nwanyi? Archetypal teenage cruelty, he said, was one thing, but the form of hate he experienced was too deliberate, it could only be bred at home. “If the child did not see an issue before the age of ten with a boy who behaves like a girl and likes to dress up during role-play, then they would not have seen it as a problem if they had not been indoctrinated to see it that way.”

He began to pray to be changed, what he now describes as a “violence” he inflicted on himself. “That was when I began to know shame. That was when I began to react: Oh, so this is what I am? This disgusting, shameful thing that deserves to be supressed with violence. Homophobia is the thing that I first discovered, and the thing that is actually taught to anybody, because it is hate. Homophobia does something to queer people. I don’t want to say it steals our childhood, I’m not going to accept that, but it does something. It colours that childhood experience. I would never allow myself actually experience a certain kind of full love because I was resisting that which was me, something I had never done until the priests. There’s a kind of rage you feel when you look back, and I’m quite lucky that all that rage — I dealt with it in my twenties. There are people who never get to deal with all those things until so much time has passed. You have to deal with this society that at every moment reminds you of your unease. We move because there’s nothing else to do.”

By the time he finished senior secondary school, Jude Dibia’s Walking with Shadows had come out. The 2005 novel was a landmark in Nigerian literature, the first to center a gay protagonist. Arinze, though, did not get to read the book until his third year at Nsukka, when a lecturer lent him a copy. He read James Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room, after a review struck a parallel between “God’s Children” and Baldwin’s story of an American man struggling with his sexuality in Paris. Giovanni’s Room was the first book he found whose central character has a consciousness that was overtly queer. By then, President Goodluck Jonathan had signed the Same-Sex Marriage Prohibition Act into law, in a desperate, futile bid at re-election.

It was January of 2014, and Ifeakandu was in the hostel when he read the news. The Anti-Gay Law criminalized same-sex relationships with a 14-year jail term. In some states, including his home state of Kano, it was punishable by stoning and assault. Shaken, he walked to the dust-laden school stadium and let himself cry. It was already so difficult, and now the law encouraged open persecution.

The Nsukka campus was both a haven for LGBTQ+ students and a hotbed of homophobia. Some nights, shouts of “Homo, homo!” rang through the dorms, as boys beat gay boys and tried to lynch them. Whenever it happened, Ifeakandu, curled up in his room while his roommates leapt out to watch the drama, had panic attacks.

“We’re already facing that violence and then you come and make a law.” He was angry. “It’s the lack of thought, for me. The lack of responsibility. But then again, a lot of us reacted by being more of ourselves. Of course, there were also a lot of people who became more hidden and even began to persecute those who dared to be themselves. It was a very fraught time and people who could not handle it took it out on others.”

He is saddened that, a decade later, the law still stands, with no talk of repeal. “I just expect that they would have taken time to rethink. It’s tragic. But then you have to accept that that’s life. You can’t dictate the speed with which things move. But is it in motion? Definitely. And that is what matters, that motion.”

In 2016, he founded 14, the first LGBTQ+ art collective in Nigeria. The editors included friends — among them, Otosirieze, Ebenezer Agu, and Kelechi Njoku — and 14 published two anthologies, We Are Flowers and The Inward Gaze, which proved popular for their mix of beautiful writing, photography, and art. The collective was part of the vanguard for the emerging generation of queer writers.

All that is why he does not quite understand fiction writers who are queer but do not write stories exploring queer realities. “I’m just, like, this is a waste of time, you know? Why are you wasting your time? Why are you wasting our time? I believe that to counter what Nigeria has done to us or is trying to do to us, because it has not done it — what Nigeria is trying to do to us is to keep us erased — for me, it’s like, how do we correct that if we are not actually telling our own stories, if we’re not putting it out there? Like, putting ourselves out there?”

He continued. “The queer babies need literature. They deserve literature, and they deserve good literature. Which is what’s so exciting about what’s happening now. And we need more of it. We need an even better quality of it. We need to have a plethora, we need to have more, multiple voices sort of speaking to that Nigerian queer experience. Speaking to, you know, our dreams, speaking to our fears, speaking to everything. Our desires, our fantasies. Even if those fantasies are fantasies of elsewhere. I think it’s very vital.”

When queer writers are successful, he believes, the conversations around their realities are stalled by too much noise and not enough depth. “We need to have these real conversations where we’re talking about what we imagine our society should look like. I think it’s our role as writers, as artists, to articulate what the condition is. So I wish we could get into the nitty-gritty of things. Our queer experience is not uniform. Some of us come from poor homes, some of us come from middleclass homes. Some of us have always been Afropolitan, and some of us are new to this Afropolitan life. All these things mean something for how we navigate the world as a queer person.”

As potent as fiction is in combating queer erasure, Ifeakandu believes that stories achieve little without the supplement of living openly. “There are things like activism. And that political involvement can just be you being, like, ‘Hey, everybody in this village, this is who I am.’” There is nothing obligatory about “coming out,” but he considers it a delusion to maintain that it does not serve an important role.

“On the one hand, we’re doing our work and our work is speaking and that work has to speak, right? I mean, because it’s so easy to sort of vilify something when it’s only an idea. And you call it ‘sin.’ You call it ‘evil.’ You call it ‘atrocity.’ You call it ‘disgusting.’ Now let’s actually put faces and names to it. Now let’s leave it between you and God, what you’re going to do with this piece of information you got. Now you’ve looked at a human being, let’s see what you do with what you see.”

In three years at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, first as an MFA student and then as an adjunct professor, Ifeakandu read America. He loved the country’s multiculturalism but not its thick sense of individualism. The country was real, there was much to enjoy, and it fulfills some of its promises, but there were also indignities to endure. He missed home.

Iowa is notoriously isolated. Fortunately, the Writer’s Workshop is a large one. That many students meant that the weekends were entertaining. At the parties, “I felt like that was the place where I became freer.”

“Imagine if we didn’t have that, and then the networks of gossip,” he told me. “People might think it’s a joke, but as a grad student, it’s very important to have a social life because a lot of grad students don’t have that. I think what I loved about the program was they allowed us to focus on our writing, and they understood that the writing was not you at your desk alone. It’s also you going to choir practice. It’s you having time to sort of do nothing.”

America also meant more books: Colm Toibin, Edmund White, Garth Greenwell, more James Baldwin. He enrolled in a PhD program at Florida State University, but dropped out shortly after, burnt out from the exertion of his book release and tour. Worse: he could not write.

Returning to Nigeria gave him grounding. He could write again. Last year, “Happy Is a Doing Word” won an O. Henry Prize. Months later, he signed a deal for his second book, a novel currently titled Say You’re Here. It’s partly set in America.

When we spoke in January, he told me he was searching for a choir; it is something of a tradition to join one in every place he settles. His love for it is a refrain in our conversation. He said to me: “Harmony, the movement of chords through your body as you sing while listening to your fellow chorister; rehearsals, complex anthems and the process of mastering them with your friends.” He finds it incredibly fulfilling.

Unsurprisingly, he prefers a choir unaffiliated with a church. Nigeria’s pervasive anti-gay sentiment stems largely from its religious institutions, and Ifeakandu, with his strong criticism of his Anglican Church, is familiar with the friction. Once, he told a member of his parish in Sabon Gari that there was nothing new he could be told about the Bible in its relation to queerness. For much of his life, he’d sat in pews and listened to sermons. “It is your turn to listen,” he said.

Ifeakandu has an agnostic outlook, but he does not think religion and gay love are irreconcilable. “If the people who are the custodians of the church — if they really cared, they would go looking for the truth. And the truth is incontrovertible. They would go looking for the facts. They are not just leaders of spiritual beings who want to go to heaven, they are also leaders of people who have to live a life on earth. It is their job to encourage people to be better, not spew falsehoods. These are things that, with more awareness and with a shift in social attitude, the Church will gradually sort of reconfigure itself around. The Church should be the catalyst for real social change. But it’s not. It’s just a house of oppression, that’s what it is. That polarity is going to be reconciled, whether we like it or not. People are going to live their lives and Churches will be forced to conform. It’s just a matter of time. But they have a chance now to be leaders in that change.”

Where the Christian family fails him, his biological one has not. The critic Esomnofu observed “a longing for fullness throughout the collection,” one that “often manifests in the limitations of family.” In the stories, familial yearning flit between the friable and the impossibly enduring, and Ifeakandu deems the book a “love letter” to his own.

Some of them have read the book. His brother’s response to it made Ifeakandu’s head and heart “swell.” A younger cousin devoured it in one night. An uncle showed him screenshots of chats with colleagues who praised it. Another relative told him that the opening stories in the collection, “The Dreamer’s Litany” and “Happy Is a Doing Word,” made her go “from hot-hot to sad!” One of his aunts took the book to work. She keeps it on her desk and reads it slowly. When customers ask, she tells them, “O nwa m nwoke dere ya.” My boy wrote it. ♦

CORRECTION: December 7, 1:38 CT: A previous version of this story misspelt the names of D. Olu Olagoke and Garth Greenwell.

“The Prodigious Arrival of Arinze Ifeakandu” appears in The Next Generation Series, an Open Country Mag project profiling rising African writers and curators, edited by Otosirieze. The groundbreaking first issue, featuring 16 voices from nine countries, was released in April 2022.

If you love what you just read, please consider making a PayPal donation to enable us to publish more like it.

Buy Arinze Ifeakandu’s book. Open Country Mag may earn an affiliate commission.

More In-depth Stories from Open Country Mag

— How the Small University Town of Nsukka Influenced Nigerian Literature

— Umar Abubakar Sidi, a Navy Pilot, Pivoted to Writing, Spurred by Surrealists

— With the S16 Film Festival, an Arthouse Collective Locks Its Focus

More Stories from Open Country Mag‘s The Next Generation Series

— Aiwanose Odafen‘s Duology of Womanhood

— Momtaza Mehri’s Fluid Diasporas

— The Overlapping Realisms of Eloghosa Osunde

— DK Nnuro Finds His Answers

— How Romeo Oriogun Wrested Poetry from Pain

— Suyi Davies Okungbowa Knows What It Takes

— Why Tobi Eyinade Built Rovingheights, Nigeria’s Biggest Bookstore

— Remy Ngamije on Doek! and the New Age of Namibian Literature

— Ebenezer Agu on 20.35 Africa and Curating New Poetry

— In Writing Cameroonian American Experiences, Nana Nkweti Crosses Genres

— Oghenechovwe Donald Ekpeki‘s Curation of African Speculative Fiction

— Logan February on Their Becoming

— The Cheeky Natives Is Letlhogonolo Mogkoroane and Alma-Nalisha Cele‘s Archive of Intentionality

— Cheswayo Mphanza on Intertextual Poetry and Zambia’s Moment

— The Seminal Breakout of Gbenga Adesina

— Keletso Mopai Owns Her Story and Her Voice

— Troy Onyango on Lolwe and Literary Magazine Publishing in Africa

— At Africa in Dialogue, Gaamangwe Joy Mogami Lures Out Storytelling Truths

— Khadija Abdalla Bajaber on Fantasy and the Character of Kenyan Writing