Modern Anglophone African literature has seen certain years recognized as more significant than others. Take 1962, the year of the Makerere Conference, a gathering of most of the continent’s most important writers, where definitions of their literary production were proposed and challenged, inconclusively. Or four years earlier, 1958, the year Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart was published, and decades of cultural formation became tethered to a single book.

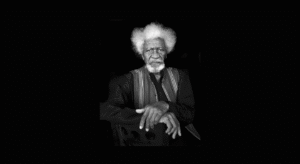

There are lesser fancied years. There is 2002, the year the Zimbabwe International Book Fair released its list of “Africa’s 100 Best Books of the 20th Century”—a list that we, by the way, must tackle for this new century—and there is, depending on your postcolonial concerns, 1986, the year Wole Soyinka became the first Black person to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature.

More time must pass to prove significance, but some of us are counting for the 21st century already. One might note 2003, the year Binyavanga Wainaina led the founding of Kwani? and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie published Purple Hibiscus, a magazine and a novel updating not just what we are allowed to write but how. If you are nerdy and Nigerian and obsessed with tiny trivia, you might dwell a bit on 2007, the year Achebe won the Man Booker International Prize and Adichie won the Women’s Prize, still the biggest awards of their literary careers, and a novella dropped from a then unknown debut writer called Teju Cole.

Or you could jump straight to an underrated year, 2013, when many important literary organisations of the last 10 years were established or picked prize winners, from the Morland Scholarship to Jalada to Writivism to Short Story Day Africa; the year that the Brunel Prize and the African Poetry Book Fund (APBF) began an overdue renaissance in a whole genre; the year that Big Afropolitan Novels became a Thing.

Or, a better acknowledged one, 2014, the year the Hay Festival collaborated with Port Harcourt as a World Book Capital and released the Africa39 anthology, predicting that the 39 featured writers under 40, representing 17 countries, “have the potential and the talent to define the trends that will mark the future development of literature” in Sub-Saharan Africa.

If we were in a rush, we would skip to 2021, the year that almost half of the major international prizes—the Nobel, the Booker, the International Booker, France’s Prix Goncourt, Portugal’s Cameos Award, PEN’s Pinter Prize—came to Africans. And then hope towards a brighter future.

But we all mark times from what they mean to us, we count from where we stand, from when we care on a new level, and so we skip back, five years, to another underrated year, the year most essential to this issue: 2016.

It wasn’t just that Adichie, buoyed by Beyonce’s borrowing of her feminism, released a then soon-to-be chapbook on Facebook, or that Warsan Shire’s poetry framed Beyonce’s album Lemonade, or that on top of all that the Swedish Academy told all of you writers to go and sit down and gave the Nobel Prize in Literature to a musician. Some might remember a lot more happening that year. It was the year that my generation emerged, and with us a new set of ideas and attitudes that over the last five years have reinvigorated literary culture in Africa and its disapora.

Most of us were living in the continent, younger millennials, all of us politically tired, many of us economically deprived, every one of us culturally thirsty. We were tired of being tired, which meant we were tired of being afraid, of not aiming for tall dreams.

In Nigeria, there was Expound, a magazine producing issues, and there was 14, the country’s first LGBTQ+ arts collective, and there was Praxis Magazine, whose poetry chapbook series that year introduced Romeo Oriogun, whose voice, shaped by his queer experience, has since taken him from the streets of Benin City to The New Yorker. Science fiction and fantasy were winning a larger audience, and as Oghenechovwe Donald Ekpeki pondered why there weren’t enough anthologies and would later provide a solution with the groundbreaking Dominion, Suyi Davies Okungbowa slowly planned the world of his first novel David Mogo, Godhunter. Elsewhere, Nnamdi Ehirim was already at work on his own novel, Prince of Monkeys. And then, in the midst of this, Gbenga Adesina won the Brunel Prize, the first time a major prize went to a young writer writing from home.

In South Africa, Letlhogonolo Mogkoroane and Alma-Nalisha Cele were about to start their podcast The Cheeky Natives, and Keletso Mopai had begun depicting the trappings of class, race, and gender that became her story collection If You Keep Digging. From that country, that year, came institutional support in the form of the Gerald Kraak Prize, which for the first time gave LGBTQ+ artists, long shut out of literary prizes, a space of their own.

In the east, in Kenya, the defunct Enkare Review started, led editorially by Troy Onyango, now of Lolwe. In Botswana, barely a literary powerhouse, Gaamangwe Joy Mogami founded the interview magazine Africa in Dialogue. In Namibia, Remy Ngamije had started his novel The Eternal Audience of One, and was running into problems that would later lead to co-founding his country’s first literary magazine Doek! The Zambian American Cheswayo Mphanza was gathering references that would feed into his poetry collection The Rinehart Frames. And back in Nigeria, laying plans for what would become the 20.35 Africa poetry collective, was Ebenezer Agu.

Meanwhile, on Instagram, Tobi Eyinade was running a bookstagram account for what would become Roving Heights, Nigeria’s biggest bookstore. Nana Nkweti, flitting between genres, had written half of the stories of Cameroonian women in her collection Walking on Cowrie Shells. Logan February was a year away from their poetry chapbooks and, later, full-length collection In the Nude. And back in the east, on the coast of Kenya, Khadija Abdalla Bajaber had begun to question why she couldn’t write a fairytale of her city, laying grounds for her novel The House of Rust.

These 16 stirring voices are not all that have exerted influence in the last five years, but through their outstanding work we hope to celebrate a generation. By placing different writers next to each other—poets and novelists, realism and science fiction and fantasy writers—and different professionals next to each other—writers, editors, online publishers, podcasters, a bookseller, an academic—we hope to showcase a range of expertise. They couldn’t be more different from each other but here they are: united in an earned vision of change and progress.

In consulting for and curating this issue, we focused on what has already been done. Each of the 16 fits into one of the following criteria:

- a curator, editor, publisher, or founder doing unprecedented, or significant, work online

- a poet or fiction writer who has published a notable full-length book

- a voice in culture, breaking out in the last five years while in the continent

Most of them produced their work from their home countries. Many of them decisively changed attitudes in important conversations, like LGBTQ+ visibility, and in whole genres, like poetry. Together, their ideas tell a different global story of African literature, one styled not in Afropolitanism but rooted in glocalism. It is a triumph, the breakout of creativity from a place of lack.

Our generation, in Africa, came of age in lack, a sense that we had been failed, that not enough was left for us, and our frustrations have over the years taken different shapes. And so we have been given different names. In 2018, I wrote a literary anthology introduction titled “The Confessional Generation.” It struck me, even then, how emotive and outspoken, how daring, how open to change we are, and, much later, how we have the most accessible power at our disposal to effect change. By 2020, it was no longer in doubt, and in the broader, worsening political context of Nigeria, we had became the Soro Soke Generation. Speak louder, we push, speak louder.

And through these profiles, these 16 are speaking the same thing in myriad ways: a vision of the future, building for a time to come, for the people rising behind them. The other side that I find, listening to these inspirers, is that they each also have their eyes on sustaining the relevant past.

Last year was five years since 2016, since we crossed from observation into participation, and this issue was initially scheduled to drop then. For the first time, our generation is considered together, in detail.

We, this platform, took our name, OPEN COUNTRY MAG, from this generation’s outspokenness, its insistence on change, on not apologizing for demanding that we be treated right. Open country, open place: this space, African literature, is now open for expression—forever. And from the moment we launched, we thought of ways to honour and document the work that these writers and curators have done, to acknowledge that their work signals the arrival of a new feeling. And here we have.

We thank our dear friends — Socrates Mbamalu, Kanyinsola Olorunnisola, Hauwa Shaffii Nuhu, Ada Nnadi, Uzoma Ihejirika — and staff — Emmanuel Esomnofu and Paula Willie-Okafor — who put in energy, time, care, and outright love into telling these inspiring stories. Without them, we have nothing.

Each of our five previous covers — Damon Galgut (Feb. 2022), Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie (Sept. 2021), Teju Cole (Jul. 2021), Maaza Mengiste (Jan. 2021), Tsitsi Dangarembga (Dec. 2020) — means something different and special to us, and some have been monumental, and so The Next Generation of African Literature comes at the rightest time, taking on layers of significance, a landmark moment not just for us and our honourees but for the culture at large.

It is our hope then, dear reader, that in this issue, in the work of these 16, you will feel the spirit of a new generation.

Part 1: The Next Generation of African Literature

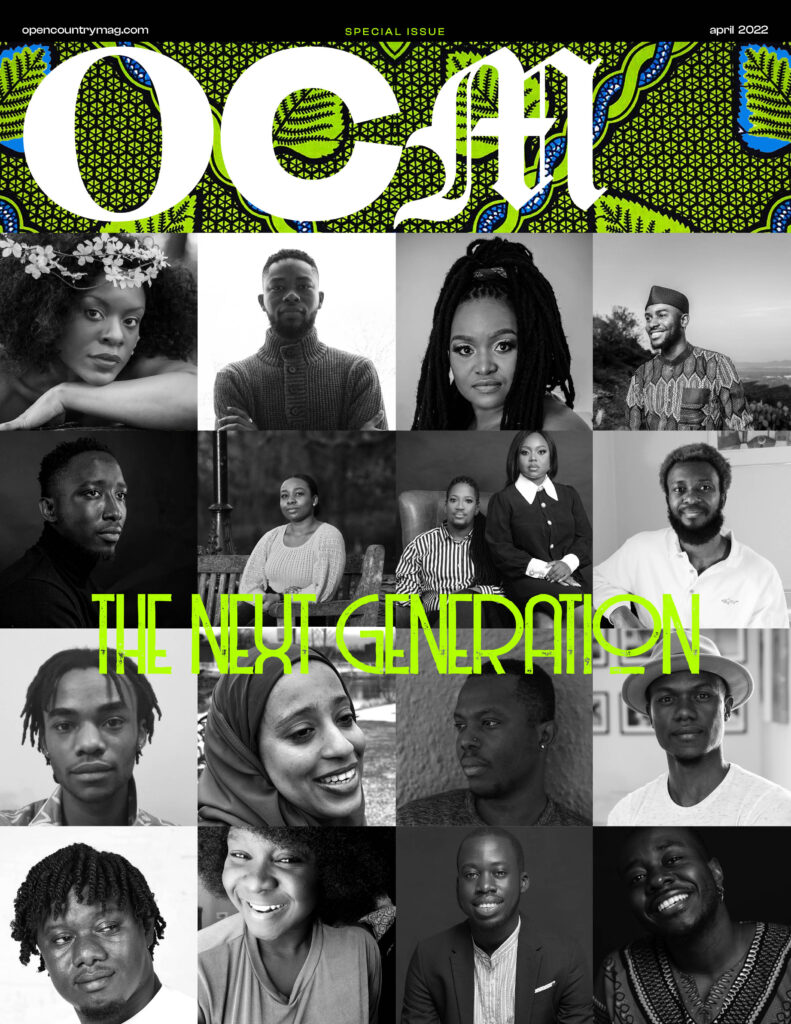

First Cover

__________________

ROMEO ORIOGUN (Nigeria)

Author of Sacrament of Bodies and Nomad, and of the chapbooks Burnt Men, The Origin of Butterflies, and Museum of Silence

By Emmanuel Esomnofu

__________________

LETLHOGONOLO MOGKOROANE and ALMA-NALISHA CELE (South Africa)

Co-founders of The Cheeky Natives podcast

By Otosirieze Obi-Young

__________________

SUYI DAVIES OKUNGBOWA (Nigeria)

Author of David Mogo, Godhunter and Son of the Storm

By Ada Nnadi

__________________

TOBI EYINADE (Nigeria)

Co-founder of Roving Heights bookstore

By Socrates Mbamalu

__________________

REMY NGAMIJE (Namibia)

Editor of Doek! and Author of The Eternal Audience of One

By Otosirieze Obi-Young

__________________

EBENEZER AGU (Nigeria)

Editor of 20.35 Africa

By Hauwa Shaffii Nuhu

__________________

NANA NKWETI (Cameroon)

Author of Walking on Cowrie Shells

By Paula Willie-Okafor

____________________________

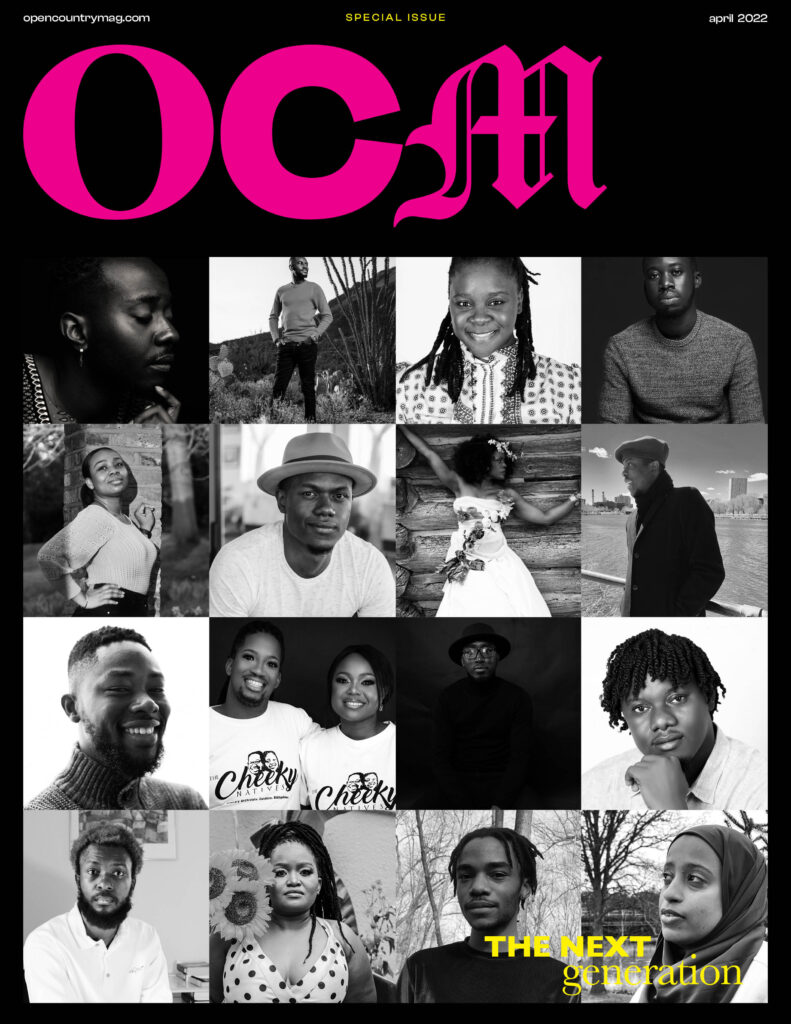

Part 2: The Next Generation of African Literature

Second Cover

____________________________

GBENGA ADESINA (Nigeria)

Author of Painter of Water and Co-founder of A Long House

By Hauwa Shaffi Nuhu

__________________

GAAMANGWE MOGAMI (Botswana)

Editor of Africa in Dialogue

By Otosirieze Obi-Young

__________________

OGHENECHOVWE DONALD EKPEKI (Nigeria)

Co-editor of Dominion: An Anthology of Speculative Fiction from Africa and the African Diaspora and of Africa Risen: A New Era of Speculation Fiction

By Kanyinsola Olorunnisola

__________________

LOGAN FEBRUARY (Nigeria)

Author of In the Nude and of the chapbooks Garlands, How to Cook a Ghost, and Painted Blue with Saltwater

By Emmanuel Esomnofu

__________________

CHESWAYO MPHANZA (Zambia)

Author of The Rinehart Frames

By Kanyinsola Olorunnisola

__________________

NNAMDI EHIRIM (Nigeria)

Author of Prince of Monkeys

By Uzoma Ihejirika

__________________

KHADIJA ABDALLA BAJABER (Kenya)

Author of The House of Rust

By Paula Willie-Okafor

__________________

KELETSO MOPAI (South Africa)

Author of If You Keep Digging

By Paula Willie-Okafor

__________________

TROY ONYANGO (Kenya)

Editor of Lolwe and Author of For What Are Butterflies without Their Wings?

By Socrates Mbamalu

__________________

Image credits

- Suyi Davies Okungbowa by Manuel Ruiz

- Remy Ngamije by Namafu Amutse

- Gbenga Adesina by Ladan Osman

- Troy Onyango by Jagero

- Khadija Abdalla Bajaber by TJ Benson

- Tobi Eyinade by Tolu Akinyemi (Poetolu)

__________________

Covers designed by Emmimade Design Agency.

__________________

If you love what you just read, please consider making a PayPal donation to enable us to publish more like it.

22 Responses